Luet oppimateriaalin englanninkielistä versiota. Mainitsit kuitenkin taustakyselyssä osaavasi suomea. Siksi suosittelemme, että käytät suomenkielistä versiota, joka on testatumpi ja hieman laajempi ja muutenkin mukava.

Suomenkielinen materiaali kyllä esittelee englanninkielisetkin termit.

Kieli vaihtuu A+:n sivujen yläreunan painikkeesta. Tai tästä: Vaihda suomeksi.

Chapter 3.4: Decisions

The Need to Select

Nearly all programs select between alternatives. For example: to determine the new favorite experience, we need to select between the old favorite experience and a newly added experience. Or: given a user input of “yes” or “no”, we want to select whether or not the program performs an operation of some sort.

One of the things we need, then, is a way to formulate a condition: Did the user select

“yes”; is this experience better than that one? You already know what we can use for

this part: the Boolean type.

The other thing we need is a way to mark commands as conditional so that the computer executes them only if a particular condition is met. It would be nice if we could also provide an alternative command to be executed in case the condition is not met.

Scala offers several tools for executing a command conditionally. In this chapter, we’ll

look at the most straighforward of these tools: the if command.

Selecting Between Two Alternatives: if

you can use the words if and else to form an expression whose value depends on a

particular condition — that is, the value depends on whether a particular Boolean

expression evaluates to true or false.

Here’s the basic idea as pseudocode:

if condition then value in case condition is met else value otherwise

It’s easy to experiment with this in the REPL:

if 10 > 100 then "is bigger" else "is not bigger"res0: String = is not bigger if 100 > 10 then "is bigger" else "is not bigger"res1: String = is bigger

The conditional expression must be of type Boolean so that it

evaluates to either true or false. In this example, the condition

has been formed with a relational operator. When the computer runs

the if command, it first evaluates the conditional expression,

which determines what happens next.

In case the condition evaluates to false, the code that follows

else is executed. The entire if expression evaluates to the

value produced by evaluating the “else branch”.

In case the condition evaluates to true, the code that

immediately follows the condition is executed. The entire if

expression evaluates to the value of this “then branch”.

Examples

Any expression of type Boolean is a valid condition. It can be the name of a Boolean

variable, for example:

val theDeathStarIsFlat = falsetheDeathStarIsFlat: Boolean = false if theDeathStarIsFlat then "Yeah right" else "No kidding"res2: String = No kidding

Or a Boolean literal, namely true or false (although this isn’t too useful):

if true then "big" else "small"res3: String = big

In all the above examples, the “then” and “else” branches were expressions of type String,

but an if certainly admits other subexpressions, too. Numbers work, for instance:

val number = 100number: Int = 100 if number > 0 then number * 2 else 0res4: Int = 200 if number < 0 then number * 2 else 0res5: Int = 0

The type of the entire if expression is determined by what

you write in the conditional branches.

Using an if as an Expression

So, an if expression has a type. You can use an if expression in any context where

that type fits. For example, you can use an if in a function’s parameter expression or

you can assign an if’s value to a variable. In case your if produces a number, you

can use the if as part of an arithmetic expression. Here are some more examples of

valid if commands:

println(if number > 100 then 10 else 20)20 val chosenAlternative = if number > 100 then 10 else 20chosenAlternative: Int = 20 (if number > 100 then 10 else 20) * (if number <= 100 then -number else number) + 1res6: Int = -1999

That being said, the last of those commands is branchy enough that you’d do better to store the intermediate values in a temporary variables before multiplying them. Like so:

val part1 = if number > 100 then 10 else 20part1: Int = 20 val part2 = if number <= 100 then -number else numberpart2: Int = -100 part1 * part2 + 1res7: Int = -1999

Practice on if expressions

Formatting an if expression

Where a single-line if expression would be long and hard to read, you can split it

across multiple lines as shown here:

val longerRemark =

if animal == favePet then

"Outstanding! The " + animal + " is my favorite animal."

else

"I guess the " + animal + " is nice enough."

end if

Note that in such a multi-line if, we indent the two branches

to a deeper level than the lines that start with if and else.

You may write an end marker at the end or omit it. It is often

omitted from if commands, but it’s perfectly fine to write it

where you think it makes your code clearer.

Mini-assignment: describe an image, part 1 of 2

In module Miscellaneous, file misc.scala, add an effect-free

function that:

has the name

describe;takes a single parameter, of type

Pic; andreturns the string "portrait" in case the given picture’s height is greater than its width, and the string "landscape" otherwise (i.e., if the image is square or wider than it’s high).

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

Finishing class Experience

You can use if in a class, thus enabling objects to make decisions when their methods

are invoked.

The chooseBetter method

From Chapter 3.3, we already have a partial implementation for class Experience. The

one part still missing is the chooseBetter method that compares two experiences and

returns the higher-rated one.

We’d like the method to work as follows:

val wine1 = Experience("Il Barco 2001", "okay", 6.69, 5)wine1: o1.goodstuff.Experience = o1.goodstuff.Experience@1b101ae

val wine2 = Experience("Tollo Rosso", "not great", 6.19, 3)wine2: o1.goodstuff.Experience = o1.goodstuff.Experience@233b80

val betterOfTheTwo = wine1.chooseBetter(wine2)betterOfTheTwo: o1.goodstuff.Experience = o1.goodstuff.Experience@1b101ae

betterOfTheTwo.nameres8: String = Il Barco 2001

In essence, chooseBetter is similar to the familiar max function (Chapter 1.6) that

picks the larger of two given numbers.

Here is class Experience with a pseudocode implementation for chooseBetter:

class Experience(val name: String, val description: String, val price: Double, val rating: Int):

def valueForMoney = this.rating / this.price

def isBetterThan(another: Experience) = this.rating > another.rating

def chooseBetter(another: Experience) =

Determine if this experience is rated higher than the experience given as * another*.

If so, return a reference to the this object. Otherwise, return the reference stored in * another*.

end Experience

And here is the method in Scala:

def chooseBetter(another: Experience) =

val thisIsBetter = this.rating > another.rating

if thisIsBetter then this else another

The word this alone constitutes an expression whose value is

a reference to the object whose method is being called.

chooseBetter’s execution ends in an if expression; the

method returns the value of that expression. Depending on

whether thisIsBetter stores true or false, the if

expression’s value will be a reference to either the active

object or the parameter object, respectively.

Improving code by calling an object’s own methods

That implementation of chooseBetter works. But class Experience is now needlessly

repetitive. Both isBetterThan and chooseBetter do the same comparison this.rating >

another.rating, so we have a double definition of what counts as “better” in our application.

In addition to being inelegant, this is unhelpful to anyone who wants to modify the application. For instance, if we wanted GoodStuff to compare experiences by their value for money rather than their rating, we’d need to modify the code in two places. In this small-scale program, the problem isn’t too bad, but larger programs with redundant code can be a nightmare to work with.

Let’s improve our code.

You’ve already seen that an object can call its own method to “send itself a message”:

this.myMethod(params). Let’s use this to compose a new version of chooseBetter:

def chooseBetter(another: Experience) =

val thisIsBetter = this.isBetterThan(another)

if thisIsBetter this else another

The Experience object asks itself: “Are you better than this

other experience?”

Now chooseBetter relies on whichever kind of comparison is defined in isBetterThan.

We have eliminated the redundancy.

A more compact solution: a method call as a conditional

A method call, too, can serve as an if’s conditional expression, as long as the method

returns a Boolean. We can use that fact to simplify chooseBetter further. This is

illustrated in the REPL session below (which assumes that wine1 and wine2 are defined

as above):

if wine1.isBetterThan(wine2) then "yes, better!" else "no, wasn’t better"res9: String = yes, better! if wine2.isBetterThan(wine1) then "yes, better!" else "no, wasn’t better"res10: String = no, wasn’t better if wine1.isBetterThan(wine1) then "yes, better!" else "no, wasn’t better"res11: String = no, wasn’t better

Here, evaluating the if entails calling the method; the value of the conditional is

whichever Boolean the method returns. After calling the method, execution continues

into one of the if’s two branches.

We’re now equipped to write a more compact implementation for chooseBetter. We don’t

need to use the temporary local variable thisIsBetter as we did above.

def chooseBetter(another: Experience) = if this.isBetterThan(another) then this else another

Our Experience class is now ready. Later, in Chapter 4.2, we’ll turn our attention to

GoodStuff’s other key class, Category.

Assignment: Odds (Part 7 of 9)

Let’s return again to the Odds program and add a method that reports an event’s odds in a format called moneyline, which is popular among North American betting agencies. This slightly curious format works as follows:

(Below, P and Q refer to the numbers that make up the

fractionalreprestentation P/Q of anOdds.)In case the event’s estimated probability is at most 50%, its moneyline number is positive and equals 100 × P ∕ Q. For instance, the moneyline number for 7/2 odds is 350, because 100 × 7 ∕ 2 = 350. This positive number indicates that if you bet 100 monetary units and win, you profit 350 units in addition to getting your bet back. A fifty–fifty scenario (1/1 odds) has a moneyline number of 100.

In case the event’s estimated probability is over 50%, its moneyline number is negative and equals -100 × Q ∕ P. For instance, the moneyline number for 1/5 Odds is -500, because -100 × 5 ∕ 1 = -500. This negative number indicates that if you want to make a profit of 100 units, you have to place a bet of 500 units.

Task description

In class Odds, add a moneyline method that returns Odds object’s moneyline

representation as an Int:

val norwayWin = Odds(5, 2) norwayWin: Odds = o1.odds.Odds@171c36b norwayWin.moneylineres12: Int = 250

In OddsTest1, add a command that prints out the first Odds object’s moneyline

number. The program’s output should now look like this:

Please enter the odds of an event as two integers on separate lines.

For instance, to enter the odds 5/1 (one in six chance of happening), write 5 and 1 on separate lines.

11

13

The odds you entered are:

In fractional format: 11/13

In decimal format: 1.8461538461538463

In moneyline format: -118

Event probability: 0.5416666666666666

Reverse odds: 13/11

Odds of happening twice: 407/169

Please enter the size of a bet:

200

If successful, the bettor would claim 369.2307692307692

Please enter the odds of a second event as two integers on separate lines.

10

1

The odds of both events happening are: 251/13

The odds of one or both happening are: 110/154

Just one new line of output.

Instructions and hints

Use an

ifexpression.moneylinemust return an integer. Drop any decimals from the result; always round towards zero. Scala’s integer division drops the decimals for you (Chapter 1.3), so the easiest solution is simply to do the arithmetic in the right order: multiply first, divide second.It’s a single word, so write

moneylinenotmoneyLine.

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

Apocalyptic programming

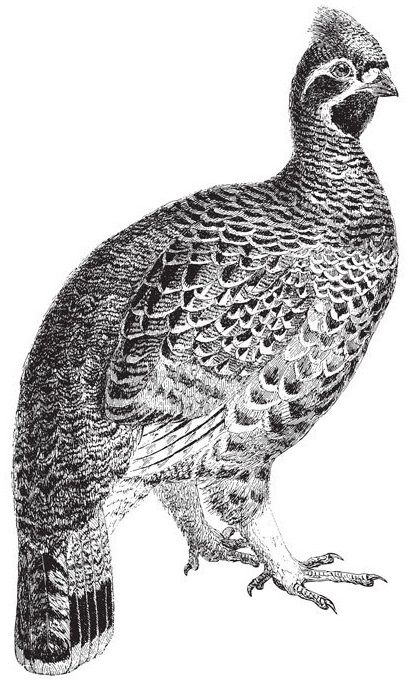

According to Finnish folklore, God punished the hazel grouse (for reasons that are disputed) and condemned it to grow smaller until the world ends. People will know that the end is nigh when the grouse is vanishingly small.

A hazel grouse.

This story has given rise to an odd Finnish idiom: a Finn may say that something “shrinks like the grouse before the apocalypse”.

Let’s model this programmatically, because why not. Here’s a class that represents grouses:

class Grouse:

private var size = 400

private val basePic = Pic("bird.png")

def foretellsDoom = this.size <= 0

def shrink() =

if this.size > 0 then

this.size = this.size - 1

def toPic = this.basePic.scaleTo(this.size)

end Grouse

You can find the class and a GUI that uses it within the IntroApps module. The GUI uses techniques from Chapter 3.1 to shrink the image of a grouse against a white background until the grouse vanishes from sight.

Your task is to read the given code and modify makePic so that it turns the

entire view black at the end. The method should therefore return:

the bird pic against a white background (as per the given code) only if calling

foretellsDoomon the grouse returnsfalse; anda fully black

endOfWorldPicif the return value istrue.

In practical terms, the only thing you need to add is an if expression in makePic.

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

Affecting Program State with an if

The branches of a selection command may specify effects on program state. They may print

text onscreen and assign to vars, for example.

An if that prints out stuff

if number > 0 then

println("The number is positive.")

println("More specifically, it is " + number)

else

println("The number is not positive.")

println("I have spoken.")

You may write more than one command in an indented branch. Those commands will be executed one after the other in case that branch is chosen.

Important: This example’s last line isn’t part of the

if command but follows it. Even though the end marker

end if has been omitted, the lack of indentation on

the last line indicates this. After executing one of the

two branches above, that last println will be executed no

matter the value of the conditional. (If we had indented the

last line, it would be executed only in case number is not

positive.)

The animations below detail how the code works, first for a positive number, then for

a negative.

The general principle behind that example

Earlier in this chapter, we used the if command to form expressions — chunks

of code that evaluate to a (meaningful) value. We used ifs to select between two

alternative values. On the other hand, in the code animated above, the if selects

between different effects on program state. Here’s the general notion summarized as

pseudocode:

if condition then commands to be executed in case the condition evaluates to true else commands to be executed in case the condition evaluates to false end if // you may omit this line

When an if affects program state, convention dictates that you break it across lines

and indent it as in the examples above, even if a branch contains just a single command.

We’ll follow this custom in O1 (as noted in our style guide).

ifs that produce Unit

The following assignment to meaninglessResult doesn’t make a lot of sense but

is worth a moment of consideration:

val meaninglessResult =

if number > 1000 then

println("Pretty big")

else

println("Not so big")Not so big

println(meaninglessResult)()

Here, the if expression has no meaningful value. The code does print one of the two

strings depending on the value in number, but it doesn’t assign anything useful in

meaninglessResult, just the Unit value (which gets printed out as empty brackets).

This is because the if’s branches end in print commands that don’t return anything

beyond Unit. It makes little sense to assign the value of such an if to a variable.

Perhaps you’ll also find it instructive to compare the above code with these two:

val result = if number > 1000 then "Pretty big" else "Not so big"result: String = Not so big println(result)Not so big

println(if number > 1000 then "Pretty big" else "Not so big")Not so big

if without else

When you use an if to affect program state, you don’t always need an else branch.

You may wish to execute one or more commands if a condition is met but do nothing

otherwise.

Of course, you could write something like this:

if condition then commands to be executed in case the condition was true else () end if

The empty else branch does nothing. But we don’t even

have to write it; we can simply omit all this.

If there’s no else branch and the conditional evaluates to false, the computer simply

disregards the rest of the if (i.e., the then branch):

if condition then commands to be executed in case the condition was true and skipped otherwise end if // you may omit this line

Here’s a more concrete example:

if number != 0 then

println("The quotient is: " + 1000 / number)

println("The end.")

This if command is effectful (it prints stuff), which is why we

use line breaks and indent the branch, despite it having just a

single command.

The second, unindented print command isn’t part of the if but

follows it. This piece of code invariably finishes by printing

"The end." no matter if number was zero or not. If it was zero,

that’s all the code prints out.

If you wish, you can also view an animation of that example:

Practice reading ifs

Assignment: FlappyBug (Part 12 of 17: Minor Adjustments)

Task description

Add two if commands to the FlappyBug game so that it meets these requirements:

The bug darts upwards only in case the key pressed by the user is the space bar, rather than any old key as in the current version.

The bug accelerates downwards (i.e., the value of its instance variable

yVelocityincreases) only if the bug is in the air (i.e., located above the ground level).

Even after falling all the way down, the bug must be able to flap its way back up.

The ground is at the same y coordinate as before, 350.

Instructions and hints

You need to modify the

onKeyDownmethod in FlappyBug’s GUI and thefallmethod in classBug. Both are described in Chapter 3.1.Just like in the earlier Flappy assignments, the

fallmethod must first increase the velocity (if above the ground level before moving) and only then move the bug.The parameter of the event handler

onKeyDownindicates which key was pressed. You can use the equality operator==to compare the parameter value withKey.Space, a constant that corresponds to the Space key.You won’t need any

elsebranches.Watch out that you don’t completely prevent the bug from moving once it falls down to the ground. Only its downward acceleration stops.

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

Combining ifs

A first try

else if chains

If you want to select among more than two alternatives, you can write an if command

within the else branch of another if:

val description = if number < 0 then "neg" else if number > 0 then "pos" else "zero"

Brackets may clarify the structure of the code:

val description = if number < 0 then "neg" else (if number > 0 then "pos" else "zero")

Perhaps the best way to highlight the multiple branches is to split the code across multiple lines and indent it:

val description =

if number < 0 then

"neg"

else if number > 0 then

"pos"

else

"zero"

To be sure, a similar chain of “else ifs” also works for selecting among multiple effectful commands:

if number < 0 then

println("The number is negative.")

else if number > 0 then

println("The number is positive.")

else

println("The number is zero.")

Mini-assignment: describe an image, part 2 of 2

Edit the describe function you wrote in misc.scala earlier so

that it returns:

the string "portrait" if the picture’s height is greater than its width;

the string "landscape" if the picture’s width is greater than its height; and

the string "square" if the picture’s height and width are exactly equal.

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

Nesting ifs

You’re free to nest if commands within each other. When you do, you need to be

especially careful about which else goes with which if. Take a look at this REPL

session:

val number = 100number: Int = 100 if number > 0 then println("Positive.") if number > 1000 then println("More than a thousand.") else println("Positive but no more than a thousand.") end if end ifPositive. Positive but no more than a thousand.

In case the number is 100, the outer if’s contents are

executed. This includes the first `println.

Within that if is another if. Since the inner if’s

condition isn’t met, the program jumps to the else branch.

The inner if’s branches are indented to a still deeper level.

When we’ve indented our code right, the if keyword is vertically

aligned with the matching else and with the (optional) end

marker. This applies both to the inner...

... and the outer if. In this example, the outer if has no

else branch. We could have omitted the end marker, but perhaps

it makes the code a bit easier to read where we have nested

ifs like this.

In the above example, the else branch is part of the “inner” if, as indicated by the

matching indentations. That else branch was executed because the outer if’s condition

was met but the inner one’s wasn’t. If you’d like to attach an else to the outer if

instead, you can do that by adjusting indentations and end markers:

if number > 0 then println("Positive.") if number > 1000 then println("More than a thousand.") end if else println("Zero or negative.") end ifPositive.

Now the outer if has two branches, and its else branch would

have been executed only if the number hadn’t been positive. Each

of the keywords in the command is indented to the same level.

In this example, the inner if has no else branch. As a

result, the program produces just the single line of output.

Practice on nested ifs

Assignment: Odds (Part 8 of 9)

Task description

The app object OddsTest2 from Chapter 3.3 creates a couple of Odds objects and

reports selected facts about them. Edit it:

Remove the

printlncommands that print the return values ofisLikelyandisLikelierThan(the ones whose output begins with the word “The”). This is because you’re about to replace these lines with new ones that produce a different printout than before.The revised

OddsTest2should check whether the event represented by the firstOddsobject is more likely than the second. Based on this check, the program should print either "The first event is likelier than the second." or "The first event is not likelier than the second." as appropriate.Next, the program should print the line "Each of the events is odds-on to happen." in case both of the events are likely. If neither event is likely, or only one is, the program should print nothing at this point.

As per our earlier definition, an event counts as likely in case the chances of it occurring are greater than those of it not occurring. That is, in case

isLikelyreturnstrue.

The final line of output, which thanks the user, should appear no matter which odds the user entered.

The example runs below detail the expected output:

Please enter the odds of the first event as two integers on separate lines. 5 1 Please enter the odds of the second event as two integers on separate lines. 1 2 The first event is not likelier than the second. Thank you for using OddsTest2. Please come back often. Have a nice day!

Please enter the odds of the first event as two integers on separate lines. 1 1 Please enter the odds of the second event as two integers on separate lines. 2 1 The first event is likelier than the second. Thank you for using OddsTest2. Please come back often. Have a nice day!

Please enter the odds of the first event as two integers on separate lines. 1 2 Please enter the odds of the second event as two integers on separate lines. 2 3 The first event is likelier than the second. Each of the events is odds-on to happen. Thank you for using OddsTest2. Please come back often. Have a nice day!

Instructions and hints

Use multiple

ifcommands.To check whether two different events are likely, you can nest one

ifinside another. Or, if you want, you can take an advance peek at Chapter 5.1 and pick out another means of combining two conditions into one.

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

Exclusivity, Exhaustivity, and Code Style

Let’s finish the chapter with some more code-reading practice that will also lead us to consider coding style. (You can score your first Category B points here, by the way.)

The questions below involve a toy function reportAge that examines a given number to

decide what it should print out. Here’s an example of intended outputs in the REPL:

reportAge(40)Adult reportAge(80)Elderly reportAge(15)Child

That is, this effectful function should print precisely one of the following:

"Adult" in case the number is 18 or more but under 70.

"Elderly" in case the number is 70 or more.

- "Child" in case the number is under 18. (Also if the

number is negative; let’s not care about that here.)

A bit more about those ageReports

In the questions above, we took it as given that each of the branches

had a println and thus each of our ifs was effectful. That’s

not a necessary assumption. We could have implemented the original

ageReport with an effect-free if expression that evaluates to one

of the strings "Elderly", "Adult", or "Child". Then we just need one

println that prints that string.

Can you rewrite ageReport in that style?

Such an alternative implementations cleanly separates the function’s

two main tasks: selecting a string and printing it. It’s also a teensy

bit more DRY, since there’s just one println for the output.

Summary of Key Points

You can use an

ifcommand to select which of two commands or sequences of commands is executed.You can also use an

ifto indicate that the execution of a piece of code is conditional: the code is executed only if specific circumstances apply.When you write an

if, you need to specify the selection condition you want. Any expression of typeBooleanis valid for that purpose.You can combine

ifcommands by sequencing them one after the other or by nesting them within each other.Combine

ifs carefully to ensure readability as well as correct behavior.elsebranches are key here.

Links to the glossary:

if;Boolean; expression; DRY.

Optional assignment: a game of precision

Write a new program where the user is supposed to click the exact center of the window with a mouse click. This simple game is over when the user manages to click, say, within three pixels of the center. At that point, the program should display an image of your choosing to signal victory.

To model the problem domain, you may wish to create a simple object

that keeps track of whether the game is over in a Boolean variable.

Also write a GUI that displays the game’s state.

No automatic feedback is available for this optional assignment.

Feedback

Please note that this section must be completed individually. Even if you worked on this chapter with a pair, each of you should submit the form separately.

Credits

Thousands of students have given feedback and so contributed to this ebook’s design. Thank you!

The ebook’s chapters, programming assignments, and weekly bulletins have been written in Finnish and translated into English by Juha Sorva.

The appendices (glossary, Scala reference, FAQ, etc.) are by Juha Sorva unless otherwise specified on the page.

The automatic assessment of the assignments has been developed by: (in alphabetical order) Riku Autio, Nikolas Drosdek, Kaisa Ek, Joonatan Honkamaa, Antti Immonen, Jaakko Kantojärvi, Onni Komulainen, Niklas Kröger, Kalle Laitinen, Teemu Lehtinen, Mikael Lenander, Ilona Ma, Jaakko Nakaza, Strasdosky Otewa, Timi Seppälä, Teemu Sirkiä, Joel Toppinen, Anna Valldeoriola Cardó, and Aleksi Vartiainen.

The illustrations at the top of each chapter, and the similar drawings elsewhere in the ebook, are the work of Christina Lassheikki.

The animations that detail the execution Scala programs have been designed by Juha Sorva and Teemu Sirkiä. Teemu Sirkiä and Riku Autio did the technical implementation, relying on Teemu’s Jsvee and Kelmu toolkits.

The other diagrams and interactive presentations in the ebook are by Juha Sorva.

The O1Library software has been developed by Aleksi Lukkarinen, Juha Sorva, and Jaakko Nakaza. Several of its key components are built upon Aleksi’s SMCL library.

The pedagogy of using O1Library for simple graphical programming (such as Pic) is

inspired by the textbooks How to Design Programs by Flatt, Felleisen, Findler, and

Krishnamurthi and Picturing Programs by Stephen Bloch.

The course platform A+ was originally created at Aalto’s LeTech research group as a student project. The open-source project is now shepherded by the Computer Science department’s edu-tech team and hosted by the department’s IT services; dozens of Aalto students and others have also contributed.

The A+ Courses plugin, which supports A+ and O1 in IntelliJ IDEA, is another open-source project. It has been designed and implemented by various students in collaboration with O1’s teachers.

For O1’s current teaching staff, please see Chapter 1.1.

Additional credits appear at the ends of some chapters.

Notice the keywords

if,then, andelse. There’s a conditional expression betweenifandthen.