Luet oppimateriaalin englanninkielistä versiota. Mainitsit kuitenkin taustakyselyssä osaavasi suomea. Siksi suosittelemme, että käytät suomenkielistä versiota, joka on testatumpi ja hieman laajempi ja muutenkin mukava.

Suomenkielinen materiaali kyllä esittelee englanninkielisetkin termit.

Kieli vaihtuu A+:n sivujen yläreunan painikkeesta. Tai tästä: Vaihda suomeksi.

Chapter 3.3: Experiences and Truths

Recap: GoodStuff

Chapter 2.1 showed how the classes of our running example, GoodStuff, work together. Before we discuss the example further, it might be a good idea to review that graphical presentation. Here it is again:

The Components of GoodStuff

In this chapter, we’ll begin exploring the Scala code that implements GoodStuff. It has the following components.

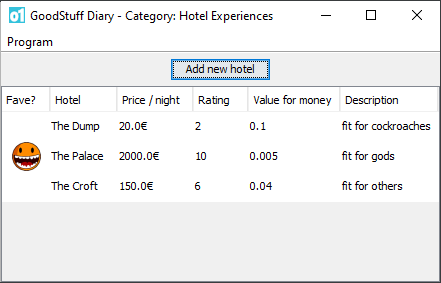

GoodStuff’s user interface. The grin-face marks the experience that the user has rated highest.

Package o1.goodstuff:

Class

Experiencerepresents entries in the diary, which describe the user’s experiences; each instance of the class corresponds to one such entry. We’ll inspect this class in this chapter and the next.Class

Categorycan be used to group multiple comparable experiences together. Each category has a name and a pricing unit (e.g., hotel experiences are priced per night). A category object also keeps track of the user’s favorite experience within that category. We’ll inspect this class in Chapters 4.2 and 4.3.

Package o1.goodstuff.gui:

CategoryDisplayWindowis a class for representing a particular sort of GUI windows. The GoodStuff application, as given, features just a single window for hotel experiences, but in principle there could be more windows of this type. The window has been implemented using a GUI library named Swing (Chapter 12.4).GoodStuffis an app object (Chapter 2.7). It’s defined inGoodStuff.scala, which is the file that you’ve used to run the program in IntelliJ.

Now, let’s look at Experience. As we do so, it will soon become apparent that we need

to learn about a new basic data type available in Scala and the more general programming

concepts associated with that type.

Read the documentation!

Locate the Scaladoc documentation for class Experience either

within the GoodStuff module in IntelliJ or through the module

link at the top of this page. Read the Scaladocs. Continue only

after you’ve read them.

You don’t need to look at the documentation of the module’s other classes now.

Experimenting with Experiences

Let’s try working with Experience objects in the REPL. To instantiate class Experience,

we need to pass in a name, a description, a price, and a rating. In the given version of

the full app, those attributes were associated with hotel experiences, but that’s just one

of many possible uses of the class. For a change, let’s create objects that correspond to

wine experiences:

val wine1 = Experience("Il Barco 2001", "okay", 6.69, 5)wine1: Experience = o1.goodstuff.Experience@a62427

The class can be used as described in its Scaladocs. Here are a couple of examples:

wine1.nameres0: String = Il Barco 2001 wine1.valueForMoneyres1: Double = 0.7473841554559043

In order for GoodStuff to figure out the favorite experience within a category, it needs

to compare experiences by their ratings. Two of the methods in class Experience are

relevant here: isBetterThan and chooseBetter. Understanding the former will help you

understand the latter, so that’s where we’ll start. Let’s try calling isBetterThan now

and get back to chooseBetter in the next chapter.

val wine2 = Experience("Tollo Rosso", "not great", 6.19, 3)wine2: Experience = o1.goodstuff.Experience@140b3c7

wine2.isBetterThan(wine1)res2: Boolean = false

The method compares the two experiences: the one the method was invoked on and the one indicated by the parameter. It returns a value that tells us whether the former object had a higher rating than the latter.

There’s something unfamiliar about this return value, though.

What does false mean, exactly? And what is its data type,

Boolean?

Truth Values and the Boolean Type

It’s extremely common for programs to deal with questions with two possible answers: Is this number larger than that one? Is this particular person already registered as a customer? Did the user tick a particular box in the GUI? Has the player chosen black or white pieces? Was the Shift key held down while the user clicked the mouse button? Has the ladybug crashed against an obstacle?

What we need is a way to represent the truth values of propositions. More specifically, we’ll use Boolean logic (Boolen logiikka), which employs precisely two truth values: true and false.

Boolean, the data type

In Scala, the words true and false correspond to “truth” and “untruth”, respectively.

These two are are reserved words, which means you can’t use them as names for variables

or other program components.

The Boolean type is defined in package scala and is therefore always available in all

Scala programs just like Int and String are. true and false are literals of type

Boolean, just like 123 and -1 are literals of type Int. (Remember: a literal is

a value that is written directly into program code.)

val popeIsCatholic = truepopeIsCatholic: Boolean = true val earthIsFlat = falseearthIsFlat: Boolean = false

Apart from true and false, no other values of type Boolean exist. (Compare: there

are countless different strings and numbers.) In Boolean logic, things can be either true

or false; there is no concept of “mostly true”, or “probably false”, or anything like that.

A Boolean literal alone forms an expression, too. The value of the expression is the truth value indicated by the literal:

falseres3: Boolean = false

Is a separate Boolean type necessary?

Could we just make isBetterThan return the string "yes" or

"no" instead of a Boolean value? Or a number: we could decide,

for example, that a return value of zero means “untrue” and any

other number means “true”?

In principle, yes. And in practice, too, the latter suggestion is

used in some programming languages. However, Scala, like many other

languages, provides a custom data type for truth values. Custom data

types help us write code that’s easier to understand; it also helps

our programming tools check for errors automatically and produce

better error messages. For instance, we can count on a Boolean

variable always storing true or false and nothing else.

Using Boolean values

You can use truth values just like you’ve used values of other types. You can store them in variables, pass them as parameters, and return them from methods:

println("The truth is " + popeIsCatholic)The truth is true

val secondPreferred = wine2.isBetterThan(wine1)secondPreferred: Boolean = false

val betterThanItself = wine2.isBetterThan(wine2)betterThanItself: Boolean = false

Numbers and strings are associated with operators such as +. One of the operators

available on Booleans is !. You can read this exclamation-mark operator as “not”.

What it does is “flip” the truth value written after it, turning false to true and

the other way around. Here’s an example:

!secondPreferredres4: Boolean = true

As reported by the REPL, the value of the entire expression !secondPreferred is true.

Note that evaluating the expression has no effect whatsoever on the variable, which

continues to store false.

Writing truth values as literals isn’t the only way to use them:

Relational Operators

Scala’s relational operators (vertailuoperaattori) form expressions that compare the values of their subexpressions.

Operator |

Meaning |

|---|---|

|

is greater than |

|

is less than |

|

is greater than or equal to |

|

is less than or equal to |

|

equals |

|

does not equal |

Two of the operators are written <= and >=. They’re not written =< or => (the

latter of which means something completely different in Scala; we’ll discuss that later).

A mnemonic: write the symbols in the order you read them: less than (<) or equal to (=).

Comparing numbers

The relational operators produce Booleans:

10 <= 10res5: Boolean = true 20 < (10 + 10)res6: Boolean = false val age = 20age: Int = 20 val isAdult = age >= 18isAdult: Boolean = true age == 30res7: Boolean = false 20 != ageres8: Boolean = false

You can use a relational operator to connect various kinds of expressions. Those subexpressions will be evaluated and their values compared to each other.

To compare for equality, you must use two equals signs. This is easy to forget before you get used to it. As you’ll recall, a single equals sign is used in Scala for some completely different purposes: to assign values to variables and at the beginning of a method definition.

The animation below features Boolean values. Can you work out what the code will print out even without first watching the animation?

Different kinds of comparisons

Take a moment to experiment with Boolean values and relational operators in the REPL.

Try applying the operators to values other than numbers. You can compare strings much

like you can compare numbers, for instance. You can also compare Booleans with each

other.

Once you’ve tried a few comparisons in the REPL, proceed to the assignments below.

Practice on relational operators

From this chapter onwards, we’ll be using truth values and comparison operators all the time. The sooner you become fluent in their use, the better, so that you don’t have to waste your mental resources thinking about these basic constructs as you work on increasingly complex programs.

To help you build that fluency, there’s a pile of tiny practice tasks below. Try and work out the answers in your head and experiment in the REPL. Don’t just guess at random or copy every answer from the REPL without thinking. Try to understand each answer and use the REPL to check your reasoning.

Mini-assignment: portraits

A picture can be shaped like a portrait or a landscape. A portrait’s height is greater than its width, whereas a landscape’s height is less than its width.

Fetch module Miscellaneous. Ignore the rest of it for now; just locate the file

misc.scala. In that file, write an effect-free function that:

has the name

isPortraittakes a single parameter of type

Picreturns

trueif the given image is taller than it’s widereturns

falseotherwise (i.e., if square or in landscape orientation).

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

On object equality

You can use the operators == and != to check whether two objects are equal. But what

exactly does equality mean for, say, experience objects?

Explore the question in the REPL as you answer the following question. (Launch the REPL in the GoodStuff module.)

As you see, even if two experience objects have identical values for their attributes, that alone isn’t sufficient to make the objects themselves “equal”.

In these examples, we used the == operator to compare the contents of two variables —

that is, to compare the references stored in two variables. Those operations don’t

actually compare what the objects are like at all. For example, wine1 == wine4 is

false, since what we have there isn’t two references to the same object but two

references to two identical but distinct objects. On the other hand, wine1 == wine3

is true, because both variables contain a reference to the one and same object; the

references lead to the same place.

More generally, how equality works on objects depends on the objects’ types. When we

write a class of our own, the default is identity comparison as shown for class

Experience above. On the other hand, many of the types in the standard Scala API have

their own type-specific definitions of equality. Buffers are a good example: two buffers

are equal if they have identical contents. The following REPL session illustrates this:

val someBuffer = Buffer(2, 10, 5, 4)someBuffer: Buffer[Int] = ArrayBuffer(2, 10, 5, 4) val anotherBuffer = Buffer(2, 10, 5)anotherBuffer: Buffer[Int] = ArrayBuffer(2, 10, 5) someBuffer == anotherBufferres9: Boolean = false anotherBuffer += 4res10: Buffer[Int] = ArrayBuffer(2, 10, 5, 4) someBuffer == anotherBufferres11: Boolean = true

Implementing Class Experience

Armed with relational operators, we’re now ready to implement class Experience. Let’s

begin with a pseudocode sketch:

class Experience(as constructor parameters, require a name, a description, a price,

and a rating; store all four in fixed-valued instance variables):

def valueForMoney = return the ratio of your rating to your price

def isBetterThan(another: Experience) = return a truth value that indicates whether

your own rating is higher than that of the

experience object you received as a parameter

end Experience

Our comparison method receives a reference to an Experience

object. In this respect, this method greatly resembles the

methods xDiff and yDiff from class Pos (Chapter 2.5).

Those methods, too, operated on two instances of the same

class: this and another instance indicated by the parameter.

(The word another has no special significance; it’s just a

name that the programmer chose for this parameter variable.)

Here is a Scala implementation:

class Experience(val name: String, val description: String, val price: Double, val rating: Int):

def valueForMoney = this.rating / this.price

def isBetterThan(another: Experience) = this.rating > another.rating

end Experience

The only new thing in this example is that the method’s return

value comes from a comparison and is therefore a Boolean.

Mini-Assignment: A Boolean Instance Variable

Preparation

Recall the classes Customer and Order from earlier chapters:

val testCustomer = Customer("T. Tester", 12345, "test@test.fi", "Testitie 1, 00100 Testaamo, Finland")testCustomer: Customer = o1.classes.Customer@a7de1d

val exampleOrder = Order(10001, testCustomer)exampleOrder: Order = o1.classes.Order@18c6974

Task description

Some object attributes can be conveniently expressed as Booleans. For example, we

might wish to record whether or not express delivery has been requested for an order.

We can represent that information as a variable isExpress on order objects:

exampleOrder.isExpressres12: Boolean = false exampleOrder.isExpress = true

Add this instance variable to class Order within the IntroOOP module. The variable’s

value should be initially false, but you should be able to adjust the value by assigning

a new value to the variable as shown above.

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

Assignment: Odds (Part 6 of 9)

We can use the newly introduced Boolean data type to extend Odds, a program that we

last worked with in Chapter 2.7.

(If you didn’t do the Odds assignments then, and don’t want to do them now, you can build on the example solutions. See the in-chapter submit forms for links.)

Task description

Write a method isLikely that determines if the event represented by an Odds object is

likely or not. We’ll say that an event is likely if the Odds of it occurring are greater

than those of it not occurring. For instance, rolling a six on a die isn’t likely, but

rolling “anything but a six” is:

val rollingSix = Odds(5, 1)rollingSix: Odds = o1.odds.Odds@d4c0c4 val notRollingSix = Odds(1, 5)notRollingSix: Odds = o1.odds.Odds@a5e42e rollingSix.isLikelyres13: Boolean = false notRollingSix.isLikelyres14: Boolean = true

Also add a method isLikelierThan that determines if one event is more likely than

another:

rollingSix.isLikelierThan(notRollingSix)res15: Boolean = false notRollingSix.isLikelierThan(rollingSix)res16: Boolean = true rollingSix.isLikelierThan(rollingSix)res17: Boolean = false

Instructions and hints

Add the methods to

Odds.scala.You can use the app object

OddsTest2to test your methods. This small program has been provided for you, but its contents have been “commented out” so that you don’t get error messages about the missing methodsisLikelyandisLikelierThanbefore you’ve implemented them. Once you’ve written the two methods in classOdds, uncomment the code inOddsTest2, then run the program.As with

OddsTest1, which we used in Chapter 2.7, the plan is forOddsTest2to invoke the methods of classOdds. Don’t copy any methods or variables fromOddsinto the test program.

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

Assignment: FlappyBug (Part 11 of 17: Game Over)

While experimenting with FlappyBug, you are sure to have noticed that the obstacle utterly fails to obstruct the bug’s movements. Let’s make the game end as soon as an obstacle touches the bug.

Preparation: the isDone method on Views

In Chapter 3.1, we studied a program displays a circle whose size grows with each click

by the user. The program featured this View object:

object clickView extends View("Click Test"):

def makePic = blueBackground.place(circle(clickCounter.value, White), Pos(100, 100))

override def onClick(locationOfClick: Pos) =

clickCounter.advance()

println("Click detected at " + locationOfClick + "; " + clickCounter)

end clickView

Let’s modify that program a bit.

You may define an isDone method on a View object. This method determines when the view

stops handling clicks, ticks, and other GUI events:

object clickViewThatStops extends View("Click Test"):

def makePic = blueBackground.place(circle(clickCounter.value, White), Pos(100, 100))

override def onClick(locationOfClick: Pos) =

clickCounter.advance()

println("Click detected at " + locationOfClick + "; " + clickCounter)

override def isDone = clickCounter.value > 10

end clickViewThatStops

isDone returns a Boolean that indicates whether the view is

“done”. That is, the return value indicates whether the GUI can

stop handling events. In this example, the GUI stops when the

counter’s value exceeds ten.

Our implementation overrides the default method, which always

returns false and therefore never stops the GUI. Hence the

override modifier (Chapter 3.1).

Each View automatically calls its own isDone method after each tick or other event to

check whether it should stop. Adjusting the frequency of those checks is possible (only)

indirectly by setting the view’s tick rate (Chapter 3.1).

Task description

Do three things:

In class

Obstacle, define a method that checks whether the obstacle is touching a bug.Use that method to define a method in class

Gamethat checks whether the player has collided with an obstacle and therefore lost the game.In

FlappyBugApp.scala, add anisDonemethod that ensures the GUI stops when the game is over.

Here are the steps in more detail:

In class

Obstacle, write an effect-free methodtouchesthat checks whether or not the obstacle is currently located where a bug is.It receives a reference to a

Bugobject as its only parameter.It returns a

Booleanvalue.It determines the distance between the obstacle in question (

this) and the given bug. The return value depends on this distance: the method returnstrueif and only if the distance is less than the sum of theradiuses of the bug and the obstacle; otherwise, it returnsfalse.It computes the distance along a straight line between the centers of the bug and the obstacle. You can use the

distancemethod from classPos(Chapter 2.5).

In class

Game, add anisLostmethod that checks whether the player has lost the game. The game is lost when the obstacle touches the bug:def isLost = this.obstacle.touches(this.bug)

Add an

isDonemethod to the GUI view. It should returntrueif the player has lost andfalseotherwise. In practice, the game should stop when the bug collides with an obstacle.See

clickViewThatStops, above, for an example of how to define anisDonemethod.In the body of

flappyView’sisDonemethod, all you need to do is call theisLostmethod that you just created.

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

A student question about effect-free methods (such as isLost)

I’m wondering about the isLost method: why

isn’t it effectful? I mean, the game is over,

isn’t that an external effect? Is it effect-free

because it only checks if the bug hits an

obstacle and doesn’t modify the game’s state

as such?

Effectful and effect-free methods are still

a bit fuzzy to me. For example, isDone [in

class View] seems pretty effectful to me,

but apparently it isn’t.

It’s true that both those methods count as effect-free. That does not mean the methods cannot impact on the behavior of the program that calls them. It’s just that those methods’ influence is indirect and happens outside the methods themselves.

Being effect-free means that just calling those methods does not cause an externally observable effect on state or behavior. The methods themselves do not change the value of any variable or diplay anything onscreen; calling them does not in itself cause the game to end or the program to terminate.

isLost merely checks something about the game’s state and reports

the result to its caller as a Boolean. isDone also merely checks

something about the model that is displayed in the view (using, as

it happens, the isLost method in this program).

What the View object does after calling those methods and

receiving the return value is a separate matter. The View uses

a private method to stop handling events when appropriate; that

private method is effectful. The basic idea is that the effectful

method calls the view’s own isDone method — and if isDone

produces true, the View stops.

Summary of Key Points

When a program needs to know “yes or no?”, it’s often convenient to use the truth values of Boolean logic: true and false. Many programming languages provide a data type for this purpose.

There are exactly two different values of type

Boolean:trueandfalseare available as literals in Scala.Relational operators yield Boolean values. You can use these operators to compare two values; you might check whether one number is smaller than another, for example.

What makes two objects count as equal depends on the data type. For some objects, equality is determined by comparing object identities, for others, by comparing one or more of the objects’ attributes.

Links to the glossary: truth value, Boolean, relational operator.

Feedback

Please note that this section must be completed individually. Even if you worked on this chapter with a pair, each of you should submit the form separately.

Credits

Thousands of students have given feedback and so contributed to this ebook’s design. Thank you!

The ebook’s chapters, programming assignments, and weekly bulletins have been written in Finnish and translated into English by Juha Sorva.

The appendices (glossary, Scala reference, FAQ, etc.) are by Juha Sorva unless otherwise specified on the page.

The automatic assessment of the assignments has been developed by: (in alphabetical order) Riku Autio, Nikolas Drosdek, Kaisa Ek, Joonatan Honkamaa, Antti Immonen, Jaakko Kantojärvi, Onni Komulainen, Niklas Kröger, Kalle Laitinen, Teemu Lehtinen, Mikael Lenander, Ilona Ma, Jaakko Nakaza, Strasdosky Otewa, Timi Seppälä, Teemu Sirkiä, Joel Toppinen, Anna Valldeoriola Cardó, and Aleksi Vartiainen.

The illustrations at the top of each chapter, and the similar drawings elsewhere in the ebook, are the work of Christina Lassheikki.

The animations that detail the execution Scala programs have been designed by Juha Sorva and Teemu Sirkiä. Teemu Sirkiä and Riku Autio did the technical implementation, relying on Teemu’s Jsvee and Kelmu toolkits.

The other diagrams and interactive presentations in the ebook are by Juha Sorva.

The O1Library software has been developed by Aleksi Lukkarinen, Juha Sorva, and Jaakko Nakaza. Several of its key components are built upon Aleksi’s SMCL library.

The pedagogy of using O1Library for simple graphical programming (such as Pic) is

inspired by the textbooks How to Design Programs by Flatt, Felleisen, Findler, and

Krishnamurthi and Picturing Programs by Stephen Bloch.

The course platform A+ was originally created at Aalto’s LeTech research group as a student project. The open-source project is now shepherded by the Computer Science department’s edu-tech team and hosted by the department’s IT services; dozens of Aalto students and others have also contributed.

The A+ Courses plugin, which supports A+ and O1 in IntelliJ IDEA, is another open-source project. It has been designed and implemented by various students in collaboration with O1’s teachers.

For O1’s current teaching staff, please see Chapter 1.1.

Additional credits appear at the ends of some chapters.

We can invoke

isBetterThanto compare the target object with another experience object. When we call the method, we pass in a reference to the other object.