Luet oppimateriaalin englanninkielistä versiota. Mainitsit kuitenkin taustakyselyssä osaavasi suomea. Siksi suosittelemme, että käytät suomenkielistä versiota, joka on testatumpi ja hieman laajempi ja muutenkin mukava.

Suomenkielinen materiaali kyllä esittelee englanninkielisetkin termit.

Kieli vaihtuu A+:n sivujen yläreunan painikkeesta. Tai tästä: Vaihda suomeksi.

Chapter 1.3: Numbers, Words, Sounds, and Pictures

Where Are We?

Now that you have an overview of programming from the previous chapters, let’s start building some concrete skills one small step at a time.

This is the short-term plan:

Between this chapter and 1.6, you’ll learn to use selected programming techniques and understand the concepts behind them. You’ll program by giving individual instructions to the computer, one by one. You’ll use the techniques as “separate pieces”: they don’t form an entire application yet.

In Chapters 1.7 and 1.8, you’ll learn to create commands of your own by combining existing ones.

From Chapter 2.1 onwards, we’ll put the pieces together and start building application programs. You’ll use all the techniques that you’ll have learned by then.

One Plus One

Practically all programs require at least a bit of elementary arithmetic: addition, subtraction, multiplication, and/or division. For instance, the GoodStuff application from the previous chapter divides numbers to determine value-for-money figures, and Pong constantly computes new coordinates for the paddles and the ball while the game is running.

Scala, like other programming languages, gives us tools for computing with numbers. For instance, you can issue this Scala command to instruct the computer to compute one plus one:

1 + 1

Simple. But where should you write such a command?

One option would be to create an entire program that makes use of this command somehow and to save that program in a file. But there’s another option that is often more convenient as we try out individual Scala commands:

The REPL

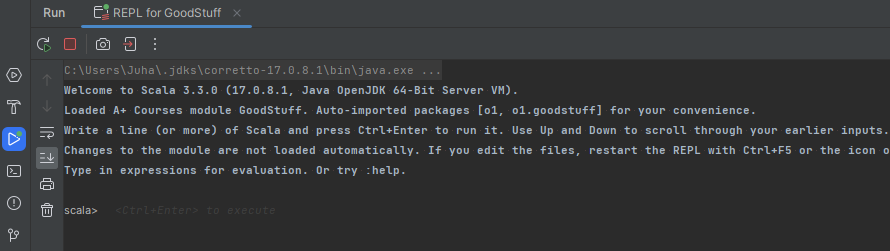

Let’s adopt a tool that is known as the REPL. Do this:

In the Project view on the left, select the module that the REPL tool will be applied to. For our purposes in this chapter, GoodStuff is the appropriate module, so select that one.

Press Ctrl+Shift+D, or select Tools → Scala REPL in the menu.

You should see a view that look essentially like this. Please make sure that its title is REPL for GoodStuff.

The REPL appears at the bottom of the IntelliJ view in the Run tab. You can type Scala code at the

scala>prompt. Press Ctrl+Enter to execute the code that you typed in. The REPL reports the results below the prompt.

This is a great place for experimentation. “REPL” is short for read–evaluate–print loop. Those words convey the basic idea:

read: You can type in bits of Scala that the REPL receives as input, or “reads”.

evaluate: The REPL runs your code as soon as it receives it. For instance, when given an arithmetic expression, the REPL performs the given calculation to produce a result.

print: The REPL reports the results of evaluation onscreen.

loop: This interaction between the user and the REPL keeps repeating as long as the user likes.

Find the scala> prompt in the REPL. Enter 1 + 1, for example, and press Ctrl+Enter.

The output will be something like this:

1 + 1val res0: Int = 2

This the Scala REPL’s way of informing you that the result of the computation is two.

res0 comes from the word result and means “result number 0” — that is, the

first result obtained during this REPL session. These numbers run from zero upwards,

which is typical in programming.

Int is the Scala name for integer numbers. In Scala, many terms are based on

English words, which is also typical in programming.

The word val (short for value) you can simply ignore for now. Many REPL

outputs begin with this word; later you’ll learn why.

Ask the REPL to compute some more values. Each result gets reported after the previous ones and labeled with a larger number:

2 + 5val res1: Int = 7 1 - 5val res2: Int = -4 2 * 10val res3: Int = 20 15 / 3val res4: Int = 5

Feel free to experiment with other arithmetic operations.

A practical hint

Press the up and down arrows on your keyboard. As you see, you can access and rerun the commands you issued previously during the same REPL session. This is often convenient.

Spaces around operators

The spaces that surround the operators in our examples are not mandatory and don’t affect the values of the arithmetic expressions. Spaces do, however, make the code a bit easier to read (once we start working with larger amounts of code). Using them is a good programming habit.

The REPL vs. a whole program

In the previous chapter, we looked at the GoodStuff application. It was stored in files, which is why it was easy for us to run and rerun the entire app at will. The acts of writing the program code and running it were unmistakeably separate from each other.

Notice how working in the REPL has a different character. The commands you enter there don’t get permanently stored anywhere. In the REPL, the same separation between writing and running a program doesn’t exist: each command is executed as soon as you finish typing it in.

On Expressions

The examples above were extremely simple, but they already involve a number of fundamental programming concepts that’ll be essential to understand as we move forward. The most important of these concepts is the expression (lauseke).

For our purposes, it’s not necessary to define the concept formally. This will suffice: an expression, in programming, is a piece of code that has a value (arvo).

So far, we’ve used arithmetic expressions, which get their values from mathetical

computations. For example, 1 + 1 is an expression; its value is the integer two.

Below is one more example in the REPL and a few other key concepts explained in terms of the example. (Reminder: hover the mouse over a boxed explanation to highlight the corresponding code.)

50 * 30val res5: Int = 1500

The subexpressions are also (simple) expressions in their own right. They are pieces of code with a value. In our example, these expressions are both literals (literaali): values that have been written “as is” into program code. You can tell the value of a literal simply by looking at it; for instance, the literal that consists of the characters five and zero has a value of fifty.

The REPL evaluates (evaluoida) the expressions that you type in. Evaluating an expression produces its value, which the REPL then reports.

Values have data types (tietotyyppi). The integer type

Int is one of the data types defined as part of the Scala

language.

It’s perfectly possible to enter just a literal as an input to the REPL, as shown below. The evaluation of such inputs couldn’t be much simpler: the literal’s value is exactly what it says on the tin:

123val res6: Int = 123

Already in this chapter — and increasingly in subsequent ones — you’ll see data types

other than Int, operators beyond basic math, and expressions more complex than literals

and arithmetic.

Dividing Numbers

Scala’s arithmetic is largely familiar from mathematics. However, there are some things that may surprise you.

Experiment with division. Try these, for instance:

> 15 / 5 res11: Int = 3 > 15 / 7 res12: Int = 2 > 19 / 5 res13: Int = 3

(Side note: Above, and from now onwards in this ebook, we won’t be repeating the

scala> prompt and val in output constantly in each

REPL example, but you get the idea. So don’t be flustered if the printouts in the

ebook don’t exactly match what you get when you enter the same commands in the

actual REPL.)

What if I want to round numbers “right”?

Scala’s way of handling integers is common in programming languages. It’s perhaps surprising how often it’s convenient that integer division works like that.

There are tools for your other rounding needs. We’ll run into them later (e.g., in Chapter 5.2).

Operator Precedence and Brackets

Some operators have precedence over others. As far as arithmetic operators are concerned, the rules should be familiar from mathematics. Multiplication is evaluated before addition, for instance:

1 + 2 * 3res0: Int = 7 5 * 4 + 3 * 2 + 1res1: Int = 27

You can use round brackets to influence evaluation order. This, too, has a familiar feel:

(1 + 2) * 3res2: Int = 9 5 * ((4 + 3) * 2 + 1)res3: Int = 75

A parenthetical warning

In school math, you may have used a different notation where one set of brackets appears inside another. For instance, you may have written square brackets around regular round brackets just for clarity of reading; each kind of bracket had the same meaning.

That won’t work in Scala code.

In Scala, round brackets are used for grouping expressions (and for a few other things). Square or curly brackets won’t do for that purpose. Those other brackets have other uses, which we’ll get to in due time.

Scala is a typical programming language in this respect. It’s common in programming that different kinds of brackets have different meanings.

On Decimals

What about decimal numbers?

In many ways, they work as you might expect. In Scala, like in most English-speaking countries, the dot is used as the decimal mark:

4.5res4: Double = 4.5 2.12 * 3.2205res5: Double = 6.82746 4.0res6: Double = 4.0

As you can tell from the above, “decimal numbers” go by the name Double in Scala.

The type is oddly named for historical reasons.

When you use values of type Double, division works more like how you might expect.

Dividing a Double by a Double yields a result that is also a Double:

999.0 / 1000.0res7: Double = 0.999

Combining numerical types

You can use Double values and Int values in the same expression:

29 / 10res8: Int = 2 29.0 / 10res9: Double = 2.9 29 / 10.0res10: Double = 2.9 30.0 / 10.0res11: Double = 3.0

If one of the operands is an integer and one is a decimal number, the result is a decimal number. That applies even if the quotient is equal to an integer.

What about more complex expressions that contain different kinds of numbers? Say,

(10 / 6) * (2.0 + 3) / 4. Here, the operators and parentheses affect the order in

which the subexpressions get evaluated. And that order determines the type of each value

produced as an intermediate result. Can you work out the value of that expression?

To check your thinking, see this interactive animation:

Computer memory and the animations in this ebook

The memory of a computer stores potentially vast amounts of data in the form of bits. As a program runs, it can reserve parts of this memory for various purposes. Each part of memory has its own unique address, a running number of sorts, that identifies that particular memory location.

The bit-level details of how computer memory works are unimportant in this introductory course. Nonetheless, even you the beginner (we presume) will greatly benefit from having a general idea of what gets stored in memory and when. This is why we use animated diagrams like the one above, which depict the effects of a program run on the contents of memory. The “areas” in these diagrams correspond to parts of computer memory that have been reserved for different purposes.

The first animated example was extremely simple, and you might have understood the expression just fine without it. Even so, it’s a good idea to get familiar with this graphical way of representing program runs, since we’ll be using similar animations to illustrate phenomena that are considerably more complex.

Strings of Characters

Besides numbers, most programs need to manipulate text. Let’s try it:

"Hi"res12: String = Hi "Hey, there's an echo!"res13: String = Hey, there's an echo!

As the REPL tells us, chunks of text or strings (merkkijono) are represented in

Scala by the String type.

A string literal is a string written into program code as is (cf. the Int and Double

literals above). String literals go in double quotation marks as shown.

(Thinking back to the previous chapter, you may recall another string literal: the quoted bit in GoodStuff that had a typo.)

If you forget the quotation marks, and you’re likely to get an error message, because the REPL will then try to interpret the text you wrote as a Scala command:

Hi-- Error: |Hi |^^ |Not found: Hi

A Command for Printing

The REPL reports the value and type of each expression, which is a useful service. But

suppose we wish to output something other than the familiar litany of resX: SomeType = value?

Scala’s println command lets us tailor the output to what we want.

println("Greetings!")Greetings! println(123)123 println(-5.2)-5.2

Even though these commands are fairly self-evident, there are several features of Scala that are worthy of attention:

Each command starts with the name of the

command. The name goes some way in defining

what behavior is caused by the command. In

this case, we print a line of text; Scala’s

println is short for print line.

Round brackets follow the name. It isn’t customary to write spaces around these brackets. (But you can, without affecting the code’s behavior.)

Within the round brackets go the command’s

parameter expressions (parametrilausekkeet),

which refine the command. In our example, each

println command is given a single parameter

expression that details what the command should

print out.

(The word “print” may lead a non-programmer’s thoughts to the sort of printers that churn out paper. But programmers also use this word about outputting text onscreen.)

A parameter expression doesn’t have to be simply a literal. For example, you might

enter the command println("Programming" + (100 - 99)). The animation below portrays

what happens when that command is executed.

As you saw, execution progressed “from inside the brackets outwards”. Later on, you’ll see how this rule of thumb holds in many situations: the parameter expressions inside the round brackets get evaluated first, producing parameter values (parametriarvo) that are then passed to the command, which uses them as it executes.

An argument about terminology

Other texts on programming may use the term “argument” to refer to either what we’ve called “parameter expressions”, or what we’ve called “parameter values”, or both. For further comments on this, please see argument on our glossary page.

Another command for printing

In addition to println, there is a print command, which works

the same, except that it doesn’t change lines at the end. In the REPL,

you can observe the difference by entering multiple commands at once.

Compare:

println("cat")

println("fish")cat

fish

print("cat")

print("fish")catfish

println is used more frequently than print is, both in general

and specifically in O1.

Try This Too

Type println(1 + 1 in the REPL, like so:

println(1 + 1

No matter how you keep hitting Ctrl+Enter, nothing much seems to happen. Is the REPL stuck?

No, it isn’t. The problem is that there’s a closing bracket missing. The REPL interprets this as an incomplete command and expects you to finish it.

Add the missing character and try again. The REPL resurrects.

So keep that in mind. You might accidentally mistype something and get that effect.

A Stringed Instrument

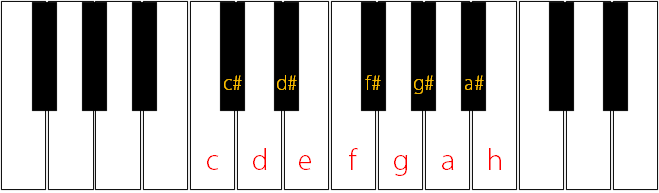

We can use strings of characters to represent text, but strings are useful for representing other things as well. Such as music. Below is a print command that outputs the first couple of bars of Ukko Nooa (“Uncle Noah”), a simple song traditionally taught to Finnish children as they start to learn the piano, as evidenced on YouTube. In our program, we represent notes as letters that correspond to the keys of a piano as shown in the picture above.

println("cccedddf")cccedddf

That was none too exciting. It would be more rewarding to play the notes than just print them out.

Let’s pick up another command. Unlike println, which is part of the Scala’s basic

toolkit, the command we use next, play, has been designed for the needs of this very

course. This command will bring some life to programs such as the string-manipulating

examples in this chapter.

(The play command is defined in O1Library, which you should have downloaded into

IntelliJ in Chapter 1.2. If you didn’t, do it now and relaunch your REPL.)

Try this:

play("cccedddf")

The command produces no visible printout. Instead, it plays the notes listed in its

String parameter on a virtual piano. Did you have sounds enabled on your computer?

Try passing other strings as parameters to play, too. For instance, you can include

spaces, which play interprets as pauses:

play("cccdeee f ffe e")

And hyphens, which play interprets as longer notes:

play("cccdeee-f-ffe-e")

Sound in O1

Here and there, we’ll make use of sound, as we just did. Obviously, this will work only if you have sounds enabled on your computer.

If you study among other people, please take a pair of headphones along.

If you don’t have access to headphones, you can use println

instead of play. Sections of this ebook will be duller for it,

but you won’t endanger your course performance.

We don’t require O1 students to have musical ability.

A note about notes

play uses “European” names for notes. This means that what is

known as a B note

in many English-speaking countries is known as H instead. Here’s an

example:

play("cdefgah")

The character b denotes flat notes. This plays an E-flat, for

instance:

play("eb")

The character ♭ works in place of b, if you prefer.

Strings attached

With numbers, + stands for addition, but the operator has a different meaning when

strings are involved. You can use it to put strings together:

"apple" + "pen"res14: String = applepen "REPL with" + "out" + " a cause"res15: String = REPL without a cause

Spaces inside the quotation marks do affect the result.

Of course, the same operator works fine even in a parameter expression:

println("Uncle Noah, Uncle Noah," + " was an upright man.")Uncle Noah, Uncle Noah, was an upright man.

play("cccedddf" + "eeddc---")

String multiplication

Another way to change octaves

In addition to supporting < and > as just described, play

lets you mark an octave number for any individual note. You may

use the numbers from 0 to 9; the default octave is number 5.

The following two commands have the same effect, for instance:

play(">cd<<e")play("c6d6e4")

This is unimportant as such, since it’s specific to a particular

music-playing command created for the purposes of this course.

But if you choose to mess around with play just for fun, you

may find it convenient to mark octaves as numbers.

Pictures and Packages

GoodStuff marks the favorite experience with a picture of a grinning face. Pong displays the paddles as pictures of rectangles and the ball as a picture of a circle. Programs manipulate pictures.

Displaying a picture

Let’s use Scala to load an image from a network address. Try it.

Pic("https://en.wikipedia.org/static/images/project-logos/enwiki.png")res16: o1.gui.Pic = https://en.wikipedia.org/static/images/project-logos/enwiki.png

Note the capital P. Pic is the name of a data type for

representing images, and it’s spelled in upper case just as

String and Int are.

We pass an address as a parameter. We represent the address as a string literal and therefore enclose it in quotation marks.

The package name o1 indicates that we’re again using a tool

created for this course. Not to worry, though: as you use these

tools, you are sure to pick up general principles that are

useful outside O1 as well.

We get a value of type Pic that holds image data loaded from

the net.

Where did that get us? A particular image is now stored in your computer’s memory, but

we didn’t get to see it. One easy way to display an image is show, which works for

pictures much like play did for sounds. See below for an example.

show(Pic("https://en.wikipedia.org/static/images/project-logos/enwiki.png"))

The image appears in a separate little window in the vicinity of the top-left corner of your screen. Click it or press Esc to close the window.

In the preceding example, we loaded the picture from the net. You can also load an image from a file stored on your computer’s disk drive. Like so:

show(Pic("d:/example/folder/mypic.png"))

You can pass in a path to a local image file. (This is just an example path to a file that could be located on someone’s computer. If you try the code, replace that with a path to some existing image file on your computer.)

On the other hand, it’s often not necessary to write the full path. If the image

file is located within an active module, there is a simpler way. Assuming you

launched the REPL in the GoodStuff module, the following will also work, since

face.png is a file within that module.

show(Pic("face.png"))

Colored shapes

The Pong game is an example of a program whose graphics are based on familiar geometric shapes. O1Library makes it easy to define such shapes in different colors. Let’s play with these tools a bit.

Let’s start with colors. You can refer to common colors simply by their English names:

Blueres17: o1.gui.Color = Blue Greenres18: o1.gui.Color = Green DarkGreenres19: o1.gui.Color = DarkGreen

Colors have the type Color.

Let’s use the circle command to create a blue circle:

circle(200, Blue)res20: o1.gui.Pic = circle-shape

Two parameter expressions go in the round brackets: the size and color of the circle.

The command produces an image of a circle whose diameter is 200

“picture elements” commonly known as pixels. The image has

the Pic data type that’s already familiar from above.

Any value of type Pic is a valid parameter for show. Instead of an image from the net

or your local drive, you can show a circle whose attributes you define as Scala code:

show(circle(200, Blue))

Experiment with other colors and shapes. For instance, here’s a rectangle, and its friend, and an isosceles triangle:

show(rectangle(200, 500, Green))show(rectangle(500, 200, Red))show(triangle(150, 200, PhthaloBlue))

About the REPL

Perhaps you have wondered whether the REPL is a tool for students/beginners only rather than for serious professionals.

No, it isn’t.

Many professionals, too, use a REPL to experiment and sketch out solutions. Besides, even serious professionals are students as they familiarize themselves with new programming languages and program components created by others.

Complex program components can be used in the REPL, including the components of specific applications. Even though we haven’t practiced coding much yet, you can already easily use the REPL to experiment with a component of an existing program. Try the following if you want.

The GoodStuff GUI in the REPL

In the previous chapter, you launched the GoodStuff GUI from IntelliJ’s menu. It’s also possible to display the GUI window by entering the following commands in the REPL.

(For this code to work in the REPL, you need to have launched the REPL within the GoodStuff module. For that to happen, make sure you have selected GoodStuff in the Project view or have one of the module’s files active in the editor when you hit Ctrl+Shift+D.)

val testWindow = CategoryDisplayWindow(Category("Hotel", "night"))

testWindow.visible = true

Here’s a brief explanation: This is how we tell the computer to create a new category of experiences for hotels (or whatever you choose, if you replace the string literals with something else) and a new GUI window that enables you to record new experiences.

The exact meaning of the example code will be clearer to you after the first couple of weeks of O1.

Summary of Key Points

You can combine integers (

Int), decimal numbers (Double), and arithmetic operators to form arithmetic expressions.An expression is a piece of code that has a value. To evaluate an expression is to determine the expression’s value.

You can use the type

Stringto form expressions whose values are strings of characters, such as text.You can use the

printlncommand to output strings or other values.The

o1package gives us tools for playing notes represented as strings (play) and working with images (Pic,show,circle,Red, etc.).The REPL environment is great for experimenting with new programming techniques, testing, and learning.

During the first weeks of O1, you’ll find out how to use the basic data types, expressions, and operations from this chapter for building GoodStuff and other applications.

Links to the glossary: REPL; expression, value, to evaluate, literal; operator; data type; string; to print; parameter expression, parameter value (or argument).

Below is a diagram of the most important concepts that we’ve covered and their main relationships. We’ll add to this diagram later.

Learn the concepts in this chapter!

Many of the terms and concepts introduced in this chapter are central to O1. Not simply for their own sake, but because you can use these concepts to make sense of programming phenomena. Knowing the terminology will help you both read this ebook and communicate with other programmers (such as your student pair or the teaching assistants). Pay particular attention to the concepts in the diagram above.

But it’s even more important that...

... you get a feel for programming in practice. The REPL is great for this. Don’t hesitate to try things in the REPL, including things that aren’t specifically suggested in these chapters.

Feedback

Please note that this section must be completed individually. Even if you worked on this chapter with a pair, each of you should submit the form separately.

Credits

Thousands of students have given feedback and so contributed to this ebook’s design. Thank you!

The ebook’s chapters, programming assignments, and weekly bulletins have been written in Finnish and translated into English by Juha Sorva.

The appendices (glossary, Scala reference, FAQ, etc.) are by Juha Sorva unless otherwise specified on the page.

The automatic assessment of the assignments has been developed by: (in alphabetical order) Riku Autio, Nikolas Drosdek, Kaisa Ek, Joonatan Honkamaa, Antti Immonen, Jaakko Kantojärvi, Onni Komulainen, Niklas Kröger, Kalle Laitinen, Teemu Lehtinen, Mikael Lenander, Ilona Ma, Jaakko Nakaza, Strasdosky Otewa, Timi Seppälä, Teemu Sirkiä, Joel Toppinen, Anna Valldeoriola Cardó, and Aleksi Vartiainen.

The illustrations at the top of each chapter, and the similar drawings elsewhere in the ebook, are the work of Christina Lassheikki.

The animations that detail the execution Scala programs have been designed by Juha Sorva and Teemu Sirkiä. Teemu Sirkiä and Riku Autio did the technical implementation, relying on Teemu’s Jsvee and Kelmu toolkits.

The other diagrams and interactive presentations in the ebook are by Juha Sorva.

The O1Library software has been developed by Aleksi Lukkarinen, Juha Sorva, and Jaakko Nakaza. Several of its key components are built upon Aleksi’s SMCL library.

The pedagogy of using O1Library for simple graphical programming (such as Pic) is

inspired by the textbooks How to Design Programs by Flatt, Felleisen, Findler, and

Krishnamurthi and Picturing Programs by Stephen Bloch.

The course platform A+ was originally created at Aalto’s LeTech research group as a student project. The open-source project is now shepherded by the Computer Science department’s edu-tech team and hosted by the department’s IT services; dozens of Aalto students and others have also contributed.

The A+ Courses plugin, which supports A+ and O1 in IntelliJ IDEA, is another open-source project. It has been designed and implemented by various students in collaboration with O1’s teachers.

For O1’s current teaching staff, please see Chapter 1.1.

Additional credits appear at the ends of some chapters.

An arithmetic expression is made up of subexpressions connected by an arithmetic operator (operaattori). Here, we used the multiplication operator

*.