Luet oppimateriaalin englanninkielistä versiota. Mainitsit kuitenkin taustakyselyssä osaavasi suomea. Siksi suosittelemme, että käytät suomenkielistä versiota, joka on testatumpi ja hieman laajempi ja muutenkin mukava.

Suomenkielinen materiaali kyllä esittelee englanninkielisetkin termit.

Kieli vaihtuu A+:n sivujen yläreunan painikkeesta. Tai tästä: Vaihda suomeksi.

Chapter 5.2: Objects Everywhere

About This Page

Questions Answered: What can I do with a String object? How do

I parse string data — a star catalog, say? So, Strings are

objects — what else is an object?

Topics: Several earlier topics are revisited from an object-oriented perspective.

What Will I Do? Read and work on short assignments.

Rough Estimate of Workload:? Two or three hours?

Points Available: A60.

Related Modules: Miscellaneous, Stars.

Notes: This chapter makes occasional use of sound, so speakers or headphones are recommended. They aren’t strictly necessary, though.

Introduction

In Chapter 2.1, we undertook to learn object-oriented programming. Since then, you’ve

created many classes and objects and used classes and objects created by others. Along

the way, it has turned out that many of the basic building blocks that we use in Scala

are objects and have useful methods; these objects include vectors and buffers (Chapter 4.2)

and Options (Chapter 4.3).

Scala is a notably pure object-oriented language in that all values are objects and the operations associated with those values are methods.

How is that? After all, we’ve also used “standalone” functions such as max and min

and written such functions ourselves. They weren’t methods of any object, right? And we

have Ints and Booleans and the like, which work with operators rather than methods,

right?

We’ll see.

Numbers as Objects

The data type Int represents integer values. This type, too, is in fact a class and

individual integers are Int objects, even though we haven’t so far viewed them from

that perspective in O1.

It’s true that Int isn’t quite a regular class. One unusual thing about this type is

that you don’t need to instantiate it explicitly; instead, you get new values of type

Int from literals. The Int class is defined as part of the core package scala,

which makes it an inseparable part of the language itself. Some of the classes in this

package, Int being one of them, are associated with “unusual” features such as a

literal notation.

That being said, Int is a perfectly normal class in that it defines a number of

methods that you can invoke on any Int object.

val number = 17number: Int = 17 number.toBinaryStringres0: String = 10001

What we did there is call toBinaryString, a method that returns a description of the

integer in the binary (base 2) number system. The base-ten integer 17 happens to be 10001

in binary format.

You can even invoke a method on an integer literal:

123.toBinaryStringres1: String = 1111011

The to method

Int objects have a method called to, which returns an object that represents all the

numbers between the target object (2 in the example below) and the parameter object (6).

val numbersFromTwoToSix = 2.to(6)numbersFromTwoToSix: Range.Inclusive = Range 2 to 6 numbersFromTwoToSix.toVectorres2: Vector[Int] = Vector(2, 3, 4, 5, 6)

The Range in our example covers the numbers 2, 3, 4, 5,

and 6 in ascending order, which is easier to see by copying

the range’s contents into a vector. (The vector takes

up more space in the computer’s memory than the Range,

because it stores each element separately whereas a Range

stores the first and last element only.)

We’ll return to to a bit further down. And we’ll put it to good use in Chapter 5.6.

The toDouble method

Here is an example of toDouble, a frequently used method on Int objects. It

returns the Double that corresponds to the Int.

val dividend = 100dividend: Int = 100 val divisor = 7divisor: Int = 7 val integerResult = dividend / divisorintegerResult: Int = 14 val morePrecisely = dividend.toDouble / divisormorePrecisely: Double = 14.285714285714286 val resultAsDouble = (dividend / divisor).toDoubleresultAsDouble: Double = 14.0

As you know, we don’t strictly need toDouble to do all that: we could have written

1.0 * dividend / divisor, for example. But toDouble says straight out what we’re

after.

abs, min, etc.

Int objects also have methods for many familiar mathematical operations. For example,

we can obtain a number’s absolute value or select the smaller of two integers as shown

below.

-100.absres3: Int = 100 val number = 17number: Int = 17 number.min(100)res4: Int = 17

Numbering indices

There are different schemes for numbering indices, but starting indices at zero is the most common approach in modern programming languages, as it has some practical benefits. Wikipedia has an article on this: Zero-based numbering.

Should indices start at 0 or 1?My compromise of 0.5 was rejected without, I thought, proper consideration.

Operators as Methods

So, numbers are objects and have methods. How do operators fit in?

Look at the documentation of class Int in the Scala API:

Browsing the documentation, you’ll find the methods introduced above: toDouble, to,

abs, and so forth. In the same list, you’ll find methods whose symbolic names look

familiar: !=, *, +, etc. (You don’t need to otherwise understand the document at

this point.)

Let’s try something:

val number = 10number: Int = 10 number.+(5)res5: Int = 15 (1).+(1)res6: Int = 2 10.!=(number)res7: Boolean = false

Arithmetic and comparisons have been defined as methods on

Int. We can tell an Int object to execute these methods as

illustrated. The output is familiar; it’s just that now we used

this somewhat more awkward notation to produce it.

Does that mean that we have an operator +, as in number + another, and, separately,

a method +, as in number.+(another)?

No. What we have is a single method and two ways to write the method call. As it turns

out, Scala permits us to leave out the dot and the brackets when calling a method that

takes exactly one parameter. The expressions number + another and number.+(another)

mean precisely the same thing. Operators are actually methods.

The concept of operator doesn’t even officially exist in Scala. (In many other languages, it does.) But it can be convenient to think of certain Scala methods — such as the arithmetic methods on numbers — as operators and omit the extra punctuation when we invoke them.

Dot notation vs. operator notation

You saw that we can omit the dot and the brackets when calling methods such as +.

The same also goes for other single-parameter methods. For example, our Category

class could contain either one of these expressions:

newExperience.chooseBetter(this.fave)

newExperience chooseBetter this.fave

The former is known as dot notation (pistenotaatio) and the latter as operator notation or infix operator notation (operaattorinotaatio).

Each notation has its benefits. Choosing between them is in part a matter of taste.

In this ebook, we use the operator notation sparingly. This is because dot notation works consistently for all parameter counts and because it highlights the target object and parameter expressions better, which is nice for learning.

We’ll mostly use operator notation for arithmetic, relational, and logic operators; we’ll

also use it in a handful of other places where it’s particularly natural. For example, most

of us would probably agree that it’s nicer to call to on an Int by writing 1 to 10

rather than 1.to(10).

In your own programs, you’re free to adopt either notation. We recommend that beginners, especially, follow the ebook’s convention. In any case, you should be aware of both notations so that you can read Scala programs written by others. Outside O1, the operator notation is somewhat more common than it is in this ebook.

“Operators” on Booleans and buffers

Logical operators (Chapter 5.1) are methods on Boolean objects.

The buffer “operators” += and -= are methods, too. You can use either operator or

dot notation to invoke them. The former is probably preferred by all and sundry.

val myBuffer = Buffer("first", "second", "third")res8: Buffer[String] = ArrayBuffer(first, second, third)

myBuffer += "fourth"myBuffer.+=("fifth")

GoodStuff revisited

In earlier chapters, you’ve seen interactive animations where GoodStuff’s objects communicate with each other via messages. In those diagrams, buffers or integers didn’t feature as objects.

As is clear by now, they too are objects: for example, an

Experience object calls the > method on an Int object to

find out which of two integers is bigger (so as to find out which

experience is better). Communication between objects thus plays

an even greater part in the program than previously discussed.

String Objects and Their Methods

At this point, it barely registers as news that String is a class, string values are

its instances, and string operators are its methods.

"cat".+("fish")res9: String = catfish

A vector contains elements of some type, each at its own index. A string contains

characters each at its own index. There is an obvious analogy between the two concepts,

and it makes sense that strings have many of the same methods that vectors and buffers

do. Strings also come with additional methods that are specifically designed for

working on character data. The examples and mini-assignments below will introduce to

some of the methods defined on Scala’s String objects.

String manipulation is very common in different sorts of programs. You’ll find the methods useful in many future chapters, and in this one, too. Once again, the point is not that you memorize the details of every method; with practice, you’ll learn to remember the common ones. The important thing is for you to get an overview of what sorts of tools are available to you.

The length of a string

The length method returns the number of characters in a string.

"llama".lengthres10: Int = 5

Getting a number from a string: toInt and toDouble

Let’s experiment with user inputs and String methods. We’ll write a tiny program that

prompts the user for a number, then reports how many digits the number has as well as

the result of another computation. The program should work like this in the text console:

Please enter an integer: 2023 Your number is 4 digits long. Multiplying it by its length gives 8092.

Here’s a first draft of the code:

import io.StdIn.*

@main def inputTest() =

val input = readLine("Please enter an integer: ")

val digits = input.length

println(s"Your number is $digits digits long.")

val multiplied = input * digits

println(s"Multiplying it by its length gives $multiplied.")

end inputTest

The above implementation “works” as shown in the two example runs below:

Please enter an integer: 2023 Your number is 4 digits long. Multiplying it by its length gives 2023202320232023.

Please enter an integer: laama Your number is 5 digits long. Multiplying it by its length gives laamalaamalaamalaamalaama.

We processed the input as a String, which is indeed necessary if we want to call its

length method. However, multiplying a string with a number doesn’t give us what we

want. It’s also displeasing that our program claims to treat any old string as if it

was a number.

In this case, just like on countless different real-world programs, we’ll need to

interpret a string that contains numerical characters as a number. For instance,

given a string that consists of the characters '1', '0', and '5', we’d like to

produce the Int value 105.

A straightforward solution is to call toInt (or toDouble, where appropriate):

val digitsInText = "105"digitsInText: String = 105 digitsInText.toIntres11: Int = 105 digitsInText.toDoubleres12: Double = 105.0

Let’s apply that to our program:

import io.StdIn.*

@main def inputTest() =

val input = readLine("Please enter an integer: ")

val digits = input.length

println(s"Your number is $digits digits long.")

val multiplied = input.toInt * digits

println(s"Multiplying it by its length gives $multiplied.")

end inputTest

The only change to the previous code is that now we interpret the numbers as an Int

for the multiplication to work.

A safer choice: toIntOption and toDoubleOption

The previous program suffered from the common problem that invalid user input can lead to missing information. Although some small programs for personal use don’t always need to cover such exceptional situations, many other programs do.

You already know that the Option type is one way to represent missing information. One

easy way to produce an Option is to call toIntOption rather than toInt; there is

also toDoubleOption and some other similar methods.

"100".toIntOptionres13: Option[Int] = Some(100) "a hundred".toIntOptionres14: Option[Int] = None "100.99".toDoubleOptionres15: Option[Double] = Some(100.99)

Mini-assignment: toIntOption

Take out the inputTest program. It’s in the Miscellaneous module under o1.inputs.

Merely replacing the toInt call with toIntOption won’t make the code work.

On the contrary, that simple modification makes the code unrunnable. (Why?)

You’ll need to deal with both valid and invalid inputs. Edit the program so that it works

as shown in the two example runs below. (Hint: use match to cover each case.)

Please enter an integer: 105 Your number is 3 digits long. Multiplying it by its length gives 315.

Please enter an integer: ten That is not a valid input. Sorry!

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

Removing whitespace: trim

The trim method is also handy when you need to process data that you’ve obtained

from an external source. It returns a string in which space characters and other

*whitespace* have been removed from both ends.

var text = " hello there "text: String = " hello there " println("The text is: " + text + ".")The text is: hello there . println("The text is: " + text.trim + ".")The text is: hello there.

The original string has some whitespace at both ends. The REPL highlights this fact by printing quotation marks around the string. The quotation marks in the output are not actually part of the string itself.

If there is no leading or trailing whitespace, trim returns an untouched string:

text = "poodle"text: String = poodle

println("The text is: " + text.trim + ".")The text is: poodle.

trim can be summarized as “removing empty characters from a string”. To be more

specific, the method does not actually change the original string but produces a

new string that contains the same characters as the original except for the omitted

whitespace. All methods on String objects are effect-free, trim included. Every

String object is immutable.

Picking out a character: apply and lift

The apply method takes an index as a parameter and retrieves the corresponding character

from the string. The numbering starts at zero, so the following code checks the fourth and

fifth letters in "llama":

"llama".apply(3)res16: Char = m "llama".apply(4)res17: Char = a

Note the return type. In Scala, individual characters are

represented by the Char class. A String is a sequence of

zero or more characters; a Char is exactly one character.

There’s also a more succinct way to access a character at an index. Try "llama"(3), for

instance.

And there is a safer way: the lift method you know from other collections.

"llama".lift(3)res18: Option[Char] = Some(m) "llama".lift(4) res12: Option[Char] = Some(a) "llama".lift(123)res19: Option[Char] = None

splitting a string

The split method divides a string into parts at the given separator. In this example,

the separator is a space:

val quotation = "There are two ways to write error-free programs; only the third one works. —A. Perlis"quotation: String = There are two ways to write error-free programs; only the third one works. —A. Perlis

val words = quotation.split(" ")words: Array[String] = Array(There, are, two, ways, to, write, error-free, programs;, only, the, third, one, works., —A., Perlis)

words(1)res20: String = are

split returns an Array, a collection of elements similar to

a vector or a buffer.

You can use the array as you’ve used a vector. The differences between these collection types are discussed in Chapter 12.1.

Any string can serve as a separator:

quotation.split("er")res21: Array[String] = Array(Th, "e are two ways to write ", ror-free programs; only the third one works. —Alan P, lis)

Letter size: toUpperCase and toLowerCase

val sevenNationArmy = "[29]<<e--------e--g--. e--. d--. c-----------<h----------->e--------e--g--. e--. d--. c---d---c---<h-----------/360"sevenNationArmy: String = [29]<<e--------e--g--. e--. d--. c-----------<h----------->e--------e--g--. e--. d--. c--- d---c---<h-----------/360 play(sevenNationArmy)

That needs to be played louder.

The function play plays upper-case notes louder than lower-case ones. There is an

easy way to produce upper-case letters:

play(sevenNationArmy.toUpperCase)

Here’s an additional example of the method and its sibling toLowerCase:

"Little BIG Man".toUpperCaseres22: String = LITTLE BIG MAN "Little BIG Man".toLowerCaseres23: String = little big man

Comparing strings: compareTo

Searching for characters: indexOf and contains

The methods indexOf and contains work much like the corresponding methods on vectors

and buffers (from Chapter 4.2). You can use them to find out if a given substring occurs

within a longer string:

"fragrant".contains("grant")res24: Boolean = true

"fragrant".contains("llama")res25: Boolean = false

"fragrant".indexOf("grant")res26: Int = 3

"fragrant".indexOf("llama")res27: Int = -1

take, drop, and company

take, drop, head, and tail are available on strings, too. These methods and

their variants are analogous to the collection methods from Chapter 4.2. Here are a few

examples:

val fromTheLeft = "fragrant".take(4)fromTheLeft: String = frag val fromTheRight = "fragrant".drop(5)fromTheRight: String = ant "fragrant".take(0)res28: String = "" "fragrant".take(100)res29: String = fragrant "fragrant".takeRight(5)res30: String = grant "fragrant".dropRight(5)res31: String = fra

val first = "fragrant".headfirst: Char = f val rest = "fragrant".tailrest: String = ragrant val firstIfItExists = "fragrant".headOptionfirstIfItExists: Option[Char] = Some(f) val firstOfEmptyString = "fragrant".drop(10).headOptionfirstOfEmptyString: Option[Char] = None

Optional assignment: string insertion

In misc.scala of module Miscellaneous, write an insert function that adds a

string into a specified location within a target string. It should work as illustrated

below.

val target = "viking"target: String = viking"

insert("olinma", target, 2)res32: String = violinmaking

insert("!!!", target, 0)res33: String = !!!viking

insert("!!!", target, 100)res34: String = viking!!!

insert("!!!", target, -2)res35: String = !!!viking

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

Speaking of strings: special characters

Chapter 4.2 mentioned in passing that you can include a newline character (a line break)

in a string by writing \n. There’s a similar notation for a number of other special

characters. Here are a few of them:

Character |

Written in literals as |

|---|---|

newline |

|

tab |

|

double quotation mark |

|

backslash |

|

For example:

println("When I beheld him in the " +

"desert vast,\n\"Have pity " +

"on me,\" unto him I cried,\n" +

"\"Whiche'er thou art, " +

"shade or real man!\"")

That produces the following output:

When I beheld him in the desert vast,

"Have pity on me," unto him I cried,

"Whiche'er thou art, shade or real man!"

As you can see, the line breaks appear where the newline characters are.

An alternative is to mark the string’s beginning and end with three double-quote characters. This tells Scala to interpret everything in between, special characters and all, as individual characters, so that there’s no need to use the backslash as an “escape”. The following code produces the same output as the one above.

println("""When I beheld him in the desert vast,

"Have pity on me," unto him I cried,

"Whiche'er thou art, shade or real man!"""")

Assignment: tempo

Introduction

The example below uses a function that takes in similar string of music as play does

and returns the tempo of that music as an integer.

tempo("cccedddfeeddc---/180")res36: Int = 180

tempo(s"""[72]${" "*96}d${"-"*39}e---f---d${"-"*39}e---f---d${"-"*15}e---f---d${"-"*15}e---f---

f#-----------g${"-"*17}&[62]${" "*104}(>c<afd)--(>c<afd)--------(afdc)--(>c<afd)-------(afdc)

${"-"*17} (>c<abfd)--(>c<abfd)--------(abfdc)--(>c<abfd)-------(abfdc)${"-"*17} (hbgfd)

${"-"*17}(hbg>fd<)${"-"*22}(>ce<hbg)---- (>d<hbge)---------- (>db<hbge)---------- (>c<hbg#e)-----

&[29]${" "*96}<<<${"c-----------"*11}cb-----------<${"hb-----------"*3}hb-----&P:a-----------

${"a--------a--a-----------"*11}/480""")res37: Int = 480

The function completely ignores the string’s actual musical content; it just extracts the tempo from the end. If there’s no tempo recorded in the string, the function returns the integer 120:

tempo("cccedddfeeddc---")res38: Int = 120

Task description

Implement tempo in misc.scala of module Miscellaneous.

Instructions and hints

The function must return an

Int, not aString, that contains the digits. The function needs to divide the string, select one of the parts, and interpret it as an integer.There are a great many ways to implement the function. Just the

Stringmethods introduced in this chapter suggest multiple solutions. Can you find more than one?You may assume that the given string has at most a single slash character

/, no more. You may also assume that in case there is a slash in the string, it’s followed by one or more digits and nothing else. In other words, you don’t have to worry about invalid inputs.

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

A better representation for songs?

In this ebook, you’ve seen some fairly long strings being passed

as parameters to play. Writing and editing strings such as these

is laborious and attracts bugs. Fortunately, you don’t have to.

If you want, you can reflect on what functions you might create to help you notate songs in O1’s string format.

You may also: 1) consider what other format we could use to represent musical notes in a program; 2) envision an application where an end user can easily write and save songs; and 3) find out what solutions are already out there.

Assignment: Star Maps (Part 3 of 4: Star Catalogues)

We concluded Chapter 4.4’s Stars assignment with this observation:

We can now display individual stars in a star map, but it would take a lot of manual work to display a map with more than a sprinkling of stars. It would be much more convenient if we could load star data into our program from a repository of some sort.

The folders test and northern within the Stars module each contain files named stars.csv.

Take a look.

The file under

testcontains a semicolon-delimited description of a few imaginary stars. You’ll learn what each number means in just a moment.The file under

northerncontains a much longer list of actual stars (originally from the VizieR service).

For now, feel free to ignore the other files under northern.

We’ll now improve our program so that it 1) reads in the star data from the files

as strings, 2) creates Star objects to represent the information encoded in those

strings, and 3) displays all the stars as graphics. The last of the three subproblems

you already solved in Chapter 4.4. The second subproblem of interpreting the string

data you’ll solve now. The first subproblem of actually handling the file has been

solved for you in the given code. (More on files later in Chapter 11.3.)

Task description

Run StarryApp. Be disappointed by its flat black output. Exit the app.

Actually, the app is very close to working nicely, but a crucial function is missing

from package o1.stars.files. That function, parseStarInfo, should do what was just

discussed: take in a string that describes a star (as the lines of stars.csv do) and

create a corresponding Star-object.

Read the documentation for parseStarInfo. It explains what each part of the input

string is expected to contain and which of those parts are significant for your task.

Then implement the function in o1/stars/files/stardata.scala.

Instructions and hints

The function has been documented as part of package

o1.stars.files.The app loads its star data from a folder, which is named at the top of

StarryApp.scala. As given, the app uses thetestfolder, which is a good choice until you feel confident that your function works. Later, you can change the folder tonorthernto produce a more impressive star map.You do not have to consider what happens if the input string doesn’t consist of six or seven semicolon-separated parts or otherwise fails to adhere to the specification. Assume that the given data string is valid.

The program will crash with a runtime error if the selected

stars.csvcontains invalid data. This would obviously be unacceptable in a proper real-world application but it will do for present purposes.

You can find helpful methods in this very chapter.

Some of the star data (the z coordinate and one of the ID numbers) are irrelevant to this assignment.

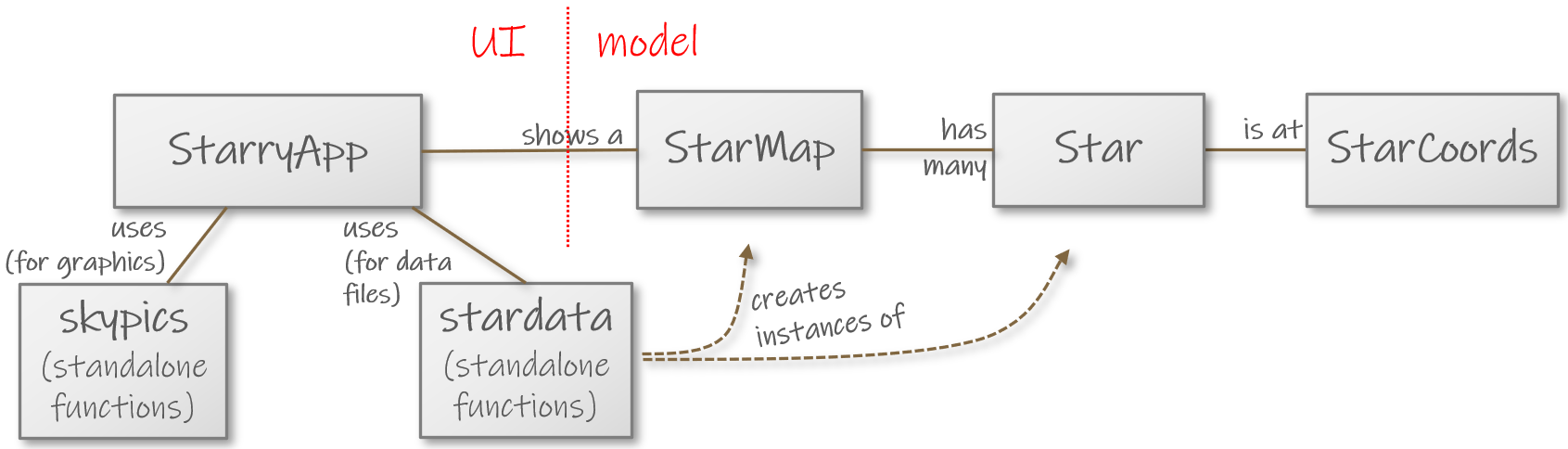

A diagram of the Stars module. In this chapter, you only implement

one function in stardata.scala.

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

Bonus Material: Rich vs. Thin Interfaces

Many similar methods — good or bad?

Here are a few student remarks on many methods on strings and collections that have come up in this and earlier chapters:

Scala seems to have a really handy set of methods for string manipulation. It’s great that [the Scala API] comes with so many methods built in.

This chapter revealed more about Scala but also made me wonder why there need to be two ways to do the same thing. It seems like that mostly creates opportunities for confusion.

Scala’s basic objects seem to have a lot methods that are fairly unnecessary i.e. do the same thing under different names.

Compared to a lot of other languages, Scala seems to have a very comprehensive set of string-handling methods.

Indeed it is not rare that a class has several methods that do similar things and that aren’t all strictly necessary. This is so for many of Scala’s core classes, too.

In other words, these classes don’t offer their users a thin interface but a rich one. This theme is discussed in Programming in Scala (which is one of the books listed on our resources page):

Thin versus rich interfaces represents a commonly faced trade-off in object-oriented design. The trade-off is between the implementers and the clients of an interface. A rich interface has many methods, which make it convenient for the caller. Clients can pick a method that exactly matches the functionality they need. A thin interface, on the other hand, has fewer methods, and thus is easier on the implementers. Clients calling into a thin interface, however, have to write more code. Given the smaller selection of methods to call, they may have to choose a less than perfect match for their needs and write extra code to use it.

It’s true that the rich interface’s user may initially feel a bit overwhelmed with the wealth of options at their disposal, but usually the riches pay off sooner rather than later.

Summary of Key Points

As an object-oriented language, Scala is pure: all values are objects.

Int,Double, andString, for example, are classes and values of those types are objects. These objects have a variety of frequently useful methods.The so-called operators are actually methods. In Scala, there are two ways to call a method: dot notation and operator notation.

Links to the glossary: object-oriented programming; dot notation, operator notation.

Does that go for other languages, too?

Scala is certainly not the only language where “everything is an object”. However, it does differ in this respect from some other object-oriented languages in common use. In the Java programming language, for example, objects and classes are used for a variety of data, but some fundamental data such integers and Booleans are instead represented as so-called primitive types. Scala’s all-encompassing object system eliminates special cases and gives the language a more consistent feel.

Feedback

Please note that this section must be completed individually. Even if you worked on this chapter with a pair, each of you should submit the form separately.

Credits

Thousands of students have given feedback and so contributed to this ebook’s design. Thank you!

The ebook’s chapters, programming assignments, and weekly bulletins have been written in Finnish and translated into English by Juha Sorva.

The appendices (glossary, Scala reference, FAQ, etc.) are by Juha Sorva unless otherwise specified on the page.

The automatic assessment of the assignments has been developed by: (in alphabetical order) Riku Autio, Nikolas Drosdek, Kaisa Ek, Joonatan Honkamaa, Antti Immonen, Jaakko Kantojärvi, Niklas Kröger, Kalle Laitinen, Teemu Lehtinen, Mikael Lenander, Ilona Ma, Jaakko Nakaza, Strasdosky Otewa, Timi Seppälä, Teemu Sirkiä, Anna Valldeoriola Cardó, and Aleksi Vartiainen.

The illustrations at the top of each chapter, and the similar drawings elsewhere in the ebook, are the work of Christina Lassheikki.

The animations that detail the execution Scala programs have been designed by Juha Sorva and Teemu Sirkiä. Teemu Sirkiä and Riku Autio did the technical implementation, relying on Teemu’s Jsvee and Kelmu toolkits.

The other diagrams and interactive presentations in the ebook are by Juha Sorva.

The O1Library software has been developed by Aleksi Lukkarinen and Juha Sorva. Several of its key components are built upon Aleksi’s SMCL library.

The pedagogy of using O1Library for simple graphical programming (such as Pic) is

inspired by the textbooks How to Design Programs by Flatt, Felleisen, Findler, and

Krishnamurthi and Picturing Programs by Stephen Bloch.

The course platform A+ was originally created at Aalto’s LeTech research group as a student project. The open-source project is now shepherded by the Computer Science department’s edu-tech team and hosted by the department’s IT services. Markku Riekkinen is the current lead developer; dozens of Aalto students and others have also contributed.

The A+ Courses plugin, which supports A+ and O1 in IntelliJ IDEA, is another open-source project. It has been designed and implemented by various students in collaboration with O1’s teachers.

For O1’s current teaching staff, please see Chapter 1.1.

Additional credits for this page

The Stars program is an adaptation of a programming assignment by Karen Reid. It uses star data from VizieR.

This chapter does injustice to music by Glenn Miller and The White Stripes. Thank you and sorry.

The guy in the desert vast was Dante Alighieri.

The return value is of type

Range. A range is an collection of numbers; like a vector, it is immutable.