Luet oppimateriaalin englanninkielistä versiota. Mainitsit kuitenkin taustakyselyssä osaavasi suomea. Siksi suosittelemme, että käytät suomenkielistä versiota, joka on testatumpi ja hieman laajempi ja muutenkin mukava.

Suomenkielinen materiaali kyllä esittelee englanninkielisetkin termit.

Kieli vaihtuu A+:n sivujen yläreunan painikkeesta. Tai tästä: Vaihda suomeksi.

Chapter 2.3: Classes of Objects

About This Page

Questions Answered: What’s a practical way to define multiple

similar objects? How do I create a new object of a particular

kind? How can I manipulate an image stored as a Pic?

Topics: Classes: objects as instances of classes; classes as

data types; instantiation. Pic objects and their methods. We’re

going to dump another heap of new concepts on you. But they will

be useful, we promise.

What Will I Do? Read and work on small programming assignments.

Rough Estimate of Workload:? Two hours, perhaps.

Points Available: A55.

Related Modules: IntroOOP. We’ll also briefly revisit Subprograms near the chapter’s end.

Classes

When a human sees a chair, the experience is taken both literally as “that very thing” and abstractly as “that chair-like thing”. Such abstraction results from the marvelous ability of the mind to merge “similar” experience, and this abstraction manifests itself as another object in the mind, the Platonic chair or chairness.

—Dan Ingalls

Imagine filling in a tax form on paper. Obviously, you won’t start with a blank page: you’ll use a predesigned sheet that tells you what information you’re expected provide. It would be incredibly inconvenient if each taxpayer had to write the form template, too, since each person provides the same kind of information. It makes sense to use a standard template and make the necessary number of copies to be filled in.

Now recall, from Chapter 2.1, the GoodStuff application and the imaginary app for course enrollment, both of which had multiple communicating objects. Many of those objects were similar to each other: there were multiple courses, multiple students, and multiple experience objects. Similar objects stored similar information and behaved the same way; each course object, for example, stored a course code, a classroom, and a list of enrolled students.

Just as with the tax forms, it would be both unnecessary and inconvenient to define every single object on an individual basis as we’ve done so far.

Using only singleton objects would have other problems as well. The programmer details each singleton object in program code, but how can they know, at the time of writing, how many objects of each kind are needed for each future program run? In most cases, the programmer simply cannot know. The objects that are needed, and their specific attributes, are determined dynamically at runtime and may depend on input that the program receives from end users. In the GoodStuff application, for example, the user defines how many experience objects should be created and what those objects’ attributes are.

What a programmer can do is define the kinds of objects that will be needed when the program is run: what types of information the program will process and what behavior is associated with each type.

This chapter deals with object types, known as classes (luokka), and the creation of objects from class definitions. Objects created this way are much more common than singleton objects are.

Our path has a familiar shape: In this chapter, you’ll experiment with classes that have already been defined for you. In future chapters, you’ll learn how to write the program code that defines a class.

Objects as Instances of Classes

The metaphor of filling a form works to clarify the relationship between classes and objects:

So, as programmers, we define:

what classes (“types of forms”) our program uses;

when to create objects of a particular class (“when to make another copy of a form template and fill it”); say, whenever the user enters information about a new experience; and

how to set the attributes of the new object (“the contents of the filled form”).

From here on in, we won’t be talking about paper forms. Instead, we’ll adopt these more technical terms:

To describe the relationship between an object and its class, we’ll say that the object is an instance (ilmentymä) of the class.

A class is a data type (or simply type) for objects (tietotyyppi) .

Creating a new instance — a new object — from a class definition is called instantiation (instantiointi).

Using a Class in Scala

Our first example class is called Employee. This class describes a type of objects

just like the single employee object that we created in the previous chapter. The only

difference — but it’s a crucial one — is that now we won’t use just one object but a

data type that represent the general concept of employee. This type enables us to create

employee objects with different names and salaries.

If we have access to a class, we can easily create new instance of it, as shown for class

Employee below. You can follow along in the REPL; the code is in module IntroOOP.

Let’s first create one new employee:

Employee("Eugenia Enkeli", 1963, 5500)res0: o1.classes.Employee = o1.classes.Employee@1145e21

We pass in constructor parameters (luontiparametri):

information that is used for initializing the object. The class

Employee is defined so that whenever we create an employee

object, we must provide a name, a year of birth, and a salary.

(The new employee works full time by default, so its working time

is 1.0.) The class’s program code uses the parameter values as

it sets the specific characteristics of the new object.

The instantiation command is an expression. The computer evaluates this expression by reserving some memory for the object’s data and by initializing the object as specified by the class.

The expression’s value is a reference to a new object. In our

example, the value is of type Employee.

When the value is an object reference, the REPL’s default behavior is to output an uninformative string. The string’s contents have to do with the way Scala handles objects and are unimportant here; right now, you can think of the string as meaning “a reference to a particular employee object”.

When we create an object, it’s often convenient also to assign the resulting reference to a variable. Below, we create another instance of the same class and define a variable that stores a reference to the new instance:

val justHired = Employee("Teija Tonkeli", 1985, 3000)justHired: o1.classes.Employee = o1.classes.Employee@704234

Now we can use the name of the variable to access the object’s methods:

println(justHired.description)Teija Tonkeli (b. 1985), salary 1.0 * 3000.0 e/month

As you saw, we just created two entirely separate employee objects. They have different attributes, but they each have some name, some year of birth, and some monthly salary.

On Instances, Variables, and References

Take a look at a couple of short animations.

That animation already showed that objects are manipulated via references, just as buffers were in Chapter 1.5. The next animation further emphasizes the importance of references.

Predict the program’s behavior as requested at the beginning of the animation below, then watch carefully to see what happens.

References to objects, references to buffers

It’s not coincidental that objects and buffers are accessed similarly via references. Buffers are objects, too. More on that in Chapter 4.2.

Questions on objects, classes, and references

The Many Purposes of a Class

Classes as data types

The term “data type” has been cropping up not just in this chapter but before we even

mentioned classes. And it’s the same concept that we’re still talking about here. For

example, class Employee is a data type for employee objects and class Experience is

a data type for the experiences in GoodStuff in the same sense as Int is a data type

for integer numbers.

When we program, we draw on data types from different sources:

Some types are closely associated with the particular application domain that we’re working on. They have been defined by ourselves or other programmers working on the same project. (E.g.,

Employee,Experience).Some types are an integral part of the programming language. (E.g.,

Int,String).And some types we adopt from a useful software library. These library classes may have been created by a third party. (E.g.,

Bufferin Scala’s standard library,Picin O1’s own library.)

Data types and singleton objects

Even a singleton object has a data type, one unique to just that object. For example, the parrot from Chapter 2.1 has its very own type:

parrotres1: o1.singletons.parrot.type = o1.singletons.package$parrot$@4e0405c9

The parrot is of a data type that no other

object has. This is shown here as parrot.type.

Whenever you define a singleton object, you implicitly define a unique data type for it.

It’s rarely necessary to expressly refer to singletons’ data types in program code.

Actually

Even the data type Int is a (somewhat special) class, but we’ll

let that lie until Chapter 5.2.

Classes as parts of a conceptual model

In Chapter 2.1, we established that one of the goals of programming is to model different problem domains. Classes open up great possibilities for conceptual modeling! Whereas objects represent individual things in a model (such as specific employees), classes represent generic concepts whose instances those specific things are (such as the generic notion of an employee). The object-oriented programmer commonly directs their attention to the classes of the program and how the classes combine to represent, in general terms, the possible worlds of objects that are created as the program runs.

Singleton objects vs. classes

It’s actually fairly rare that a programming language lets us define singleton objects in program code in the way that Scala does. In many widely used languages that support OOP, objects are always created by instantiating a class. Which is what we do in Scala, too, for the most part.

That is not to say that classes are absolutely necessary for OOP. In some languages (with JavaScript the most popular), objects are created by cloning other objects, and one object can serve as a prototype for other similar objects. You can read more about prototype-based programming in Wikipedia.

Classes as abstractions

The topic of abstraction has already surfaced in many of the preceding chapters. And again we have come across a new form of abstraction: classes are abstractions — generalizations — of objects. Furthermore, they are abstractions of the domain concepts that they represent.

Classes as parts of program code

The code of an object-oriented program written in Scala consists of the definitions of classes and singleton objects.

It’s possible to define all of a program’s classes in the same file. However, many Scala

programmers only put multiple classes in the same file if those classes are very closely

associated with each other. In O1, you’ll usually write each class in its own .scala

file.

It’s customary to match the name of each code file to the class or singleton object

defined therein. The class Employee, for example, is defined in a file named

Employee.scala, which we’ll inspect in the next chapter.

On Classes and Their Methods

A class is where we teach objects how to behave.

—Richard Pattis

In the animation of employee objects, did you notice that the objects’ attributes were stored separately from the class? And that methods were associated with the class, not with each object separately?

A class definition is shared among all objects of that type, and there is no need to duplicate its contents for each object. Each object has a known type that defines its methods.

By defining the methods of its instances, a class determines how all objects of

its type behave. For example, all instances of class Employee have the methods

monthlyCost and description, and each such object responds in the same manner when

those methods are invoked. As it does so, the object relies on its own instance-specific

attributes.

The limitations of objects

You can only command an instance of a class to do something that it knows how to do.

If you call a method, the method must be defined in the appropriate class, and you must

provide parameters as dictated by the class definition. None of the following attempts

to command an Employee object succeed, for example.

var example = Employee("Edelweiss Fume", 1965, 5000)res2: o1.classes.Employee = o1.classes.Employee@177e207

example.repairMyGiraffe("pronto!")-- Error:

|example.repairMyGiraffe("pronto!")

|^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

|value repairMyGiraffe is not a member of o1.classes.Employee

example.ageInYear(2014, 2023)-- Error:

|example.ageInYear(2014, 2023)

| ^^^^^^^^^^

| Found: (Int, Int)

| Required: Int

example.ageInYear("2023")-- Error:

|example.ageInYear("2023")

| ^^^^^^

| Found: ("2023" : String)

| Required: Int

If the method exists but you forget to pass any parameters, there’s no immediate error but the result is not what you intended and looks funny:

example.ageInYearres3: Int => Int = Lambda$1354/0x0000000801109800@3a5ce4b8

That gobbledygook essentially means that Scala has interpreted the expression

example.ageInYear as referring to a function. However, that function didn’t get called,

and the employee’s age was not determined, which indeed would have been impossible without

the value for the parameter. (The seemingly odd behavior actually does have a reasoning

behind it, but we’ll only be able to connect with it once we reach Chapter 6.1.)

Practice Using a Class

The IntroOOP module contains more than class Employee. Class PhoneBill represents

(again, in a grossly simplified manner) the money that customers owe to a telephone

operator: a single instance of the class is a single customer’s phone bill. Each

phone bill is associated with a number of phone calls (zero or more), each of which is

represented as a single PhoneCall object, that is, an instance of class PhoneCall.

Practice working with these classes in the REPL as instructed below. Both classes have already been defined for you; in this assignment, you don’t need to define them or indeed any other classes.

If you find this assignment difficult, you may wish to scroll down to the section titled Pitfalls before returning to work on the assignment.

Using class PhoneCall

Things to know about class PhoneCall:

When you create a

PhoneCallobject, you need to pass in the following constructor parameters: an initial fee (for starting the call, in euros), a price per minute (in euros), and a duration in minutes. All three are represented asDoubles.As defined in the class, each

PhoneCallobject can provide, upon request, the total price of the phone call that it represents. We can request this information from the object with the parameterlesstotalPricemethod. To determine its total price, aPhoneCallobject uses the constructor parameters that it received earlier; it also adds a surcharge for using the telecommunications network.The class has another parameterless method,

description, which produces a textual description of a phone call.

You’re free to experiment with the class in the REPL, but make sure you do at least the following.

Create a new

PhoneCallobject and define a variable to store a reference to the object.Pick a name for the variable. (For example,

callToJennyor anything you like.)Use an initial fee of 0.99 euros, a per-minute price of 0.47 euros, and a duration of 7.5 minutes.

Call the

totalPricemethod of the object you created. Observe that the return value includes a surcharge equal to 13 euro cents plus 1.3 cents per minute.Call

descriptionon your object. (In the description that the method produces, the prices are rounded to fewer decimals; that’s not important now.)

Using class PhoneBill

Things to know about PhoneBill:

When you create a

PhoneBillobject, use a single constructor parameter: the customer’s name as a string.The method

addCallexpects a reference to aPhoneCallobject as a parameter. When you invoke this effectful method on a particularPhoneBillobject, the object will add the given phone call to “itself”, that is, to the phone bill that it represents.Phone bills, too, have a

totalPricemethod that takes no parameters. It returns the sum of all the phone calls that have been previously added to the bill.The method

breakdownis also parameterless. It returns a multi-line string that spells out each phone call added to the bill.

Start by doing the following in order, then feel free to experiment as you please:

Create a single phone-bill object and a variable that refers to it. Pick any customer name you wish (e.g., your own name). Name the variable as you wish (e.g.,

myBill).Add the phone call you created earlier to the new phone bill. You should already have a variable that refers to the phone call; use its name as a parameter expression.

Add another phone call to the same phone bill:

Use an initial fee of 1.2 euros, a per-minute price of 0.4 euros, and a duration of 30 minutes.

A single line suffices to both create the phone call and add it to the bill: make the instantiating command (that begins with

PhoneCall) a parameter expression ofaddCall. This way, the reference to the newly created object will be immediately passed as a parameter to the method.

Call the phone bill’s

totalPricemethod.Call the phone bill’s

breakdownmethod.Score some points by entering the return values of

totalPriceandbreakdownin the form below.

An Updated Concept Map

This might be a good time to place the new concepts in our concept map:

Pitfalls

Among the fundamental concepts of object-oriented programming, several pitfalls await the unwary beginner. Many have fallen prey. Watch out.

Although we’ve tried to write this chapter so that it steers you clear of misconceptions, it’s perhaps best to underline some of them just to make sure.

Classes are not containers for objects

A fairly common beginner’s mistake is to think of a class as a group of objects or a storage space for objects. You might also think of objects as being located within a class in some sense. However: a class is a description of what a certain kind of objects have in common; it’s not a location for storing that kind of objects. Or, to extend our earlier metaphor: a class is “a particular form template”, not “a folderful of filled forms”.

One practical consequence of this is that you can’t use the name of a class to access, say, a list of the objects that the class “contains”. Neither does a class impose an order or organization on objects that are “located within it” (which they aren’t). Where we want to refer to objects, we generally use variables.

It is certainly common that we wish to manipulate several related objects as a group. When this is the case, we can place those objects inside a collection such as a buffer. We’ll be doing a lot of that in later chapters.

A class’s instances don’t have “names”

The instances of our employee class each had a name; the instances of a bank-account class could each have an account number; course objects could each have a course code, and so on. That being so, it’s easy to form a mistaken impression: that the instances of some classes, if not all, have a built-in name or identifier that we can use to refer to those instances in program code.

However, none of the above actually work for referring to an instance in program code. If

you write the name of an employee to the left of the dot — "Edelweiss Fume".ageInYear(2023)

— the code works precisely as badly as if you had entered the object’s salary or working

time instead of its name. The name, salary, and working time are attributes of the

object, but none of them identifies the object among all others, not even if there aren’t

any other objects with the same value for the attribute.

When we want to specify which object’s method we intend to call, the common thing to do is to use a variable to store a reference to the object, which enables us to access the object through the variable’s name. Which is what we’ve done multiple times in this chapter.

In this respect, the instances of classes differ from singleton objects. The code that

defines a singleton object gives the object a name that serves as an identifier for that

specific object. We have referred to singleton objects named account and parrot, for

example, without defining variables that refer to those objects.

To be sure, sometimes we want our program to find, among a collection of objects, the object with particular attribute value, such as a particular name or course code. That’s a separate problem that can be solved in a number of ways. We’ll discuss some of those ways in Chapters 5.5 and 9.2.

A variable that refers to an object is not the object’s name

var example = Employee("Edelweiss Fume", 1965, 5000)

Looking at this line of code as a whole, it would be natural to think that it creates an

object of type Employee and gives it the name example. That interpretation is faulty,

however. There’s rather more going on: a variable is defined, an object is created, and a

reference that points to the object is stored in the variable.

You’ve already seen that multiple distinct variables can simultaneously contain a reference

to the same place (the same object) and that even a single var can refer to different

objects at different times during a program run. So we must recognize that a name such as

example is not the name of an object but of a variable. This is illustrated in many of

the ebook’s animations.

Why don’t instances have names?

So, none of an instance’s attributes identifies it, and the name of a variable that refers to an instance is not an attribute of the instance. Why do we name variables rather than naming instances?

Two of the reasons are given below. They may seem a bit abstract now, but that’ll change as you gain more experience with object-oriented programming.

Multiple sites within a program may refer to a single object, and the object may have different “roles” in different contexts. It makes sense to use different names to refer to the object as suits each context. This is not unlike people’s roles in the real world: “the president”, “the club’s treasurer”, “my wife”, “my mother”, “some passer-by”, “the next customer”, “the customer who placed the order”, and “that passenger” may all refer to the same individual as different parties consider a person from different perspectives.

Often, we want to change which object has a particular “role” in a program while the program is running. Nevertheless, we want to use a specific name to access whichever object has that role at the moment. An example is the favorite experience recorded by the GoodStuff application, which may change during a program run. (The real-world comparison fits again: “the president”, “the next customer”, or “my wife” may refer to different individuals at different times.)

Review: manipulating instances through variables

More Practice: Pictures as Objects

In Week_1, we created images that had the Pic data type. Pic is actually the name of

a class, and each value of type Pic is an object that stores data on what appears

in the image.

The Pic type can be used for representing diverse shapes and other images. For our

convenience as we work with different kinds of Pics, package o1 provides multiple

distinct functions that create Pics. The functions circle and rectangle are

two examples: each creates a new picture object and returns a reference to the created

object. We haven’t written Pic(...) to create Pics with shapes; instead, we have

used, and will continue to use, these convenient functions.

The only thing we’ve done with a Pics so far is pass it to the show function, which

displays the image. However, that’s not nearly all we can do: these picture objects have

a wealth of methods. We’ll now take a look at a few of them.

The basic attributes of a Pic

We can query a Pic object for its width and height.

val littleCircle = circle(100, Red)littleCircle: Pic = circle-shape littleCircle.widthres4: Double = 100.0 littleCircle.heightres5: Double = 100.0 val bigger = circle(littleCircle.width * 3, Red)bigger: Pic = circle-shape bigger.widthres6: Double = 300.0

The same functionality is available on any Pic object, including ones loaded from

a file:

val loaded = Pic("ladybug.png")loaded: Pic = ladybug.png

println("The pic has a total of " + loaded.width * loaded.height + " pixels.")The pic has a total of 900.0 pixels.

“Editing” a Pic

It’s easy to rotate an image. Try this and see for yourself.

val myRectangle = rectangle(100, 200, Orange)myRectangle: Pic = rectangle-shape val rotated = myRectangle.clockwise(45)rotated: Pic = rectangle-shape (transformed) show(rotated)show(myRectangle)

The clockwise method takes in the magnitude of the rotation

in degrees.

It returns a new image object that is a rotated version of the original. The REPL reports this as shown.

Neither clockwise nor any other of a Pic’s methods

has an effect on an existing image. The original Pic

remains what it was.

The history method returns information about how a Pic has been formed:

rotated.historyres7: List[String] = List(clockwise, rectangle)

We get a report showing that the picture has been formed by making a rectangle and rotating it.

Combining Pics

Let’s create a new picture by placing two existing pictures side by side:

val first = rectangle(50, 100, Red)first: Pic = rectangle-shape val second = rectangle(150, 100, Blue)second: Pic = rectangle-shape val combination = first.leftOf(second)combination: Pic = combined pic show(combination)

The methods rightOf, above, and below work like leftOf does in the above REPL

session. Try them!

As another example, this code forms an image by arranging four copies of the same image in a two-by-two layout:

val testPic = Pic("https://en.wikipedia.org/static/images/project-logos/enwiki.png")testPic: Pic = https://en.wikipedia.org/static/images/project-logos/enwiki.png

val sideBySide = testPic.leftOf(testPic)val sideBySide: Pic = combined pic

show(sideBySide.above(sideBySide))

The virtual “ping-pong table” that you saw in Chapter 1.2’s Pong game was similarly constructed by placing shapes together.

In Week 1, you wrote a function verticalBar that returned a value of type Pic. In

the following exercises, too, you’ll write functions that return references to Pic

objects. The first and easiest of these exercises is voluntary.

An easy training problem

Write an effect-free function called twoByTwo that:

takes an image as its only parameter; and

returns(!) an image in which the given image appears four times in a two-by-two layout.

The function is an abstraction of one of the examples above: it does the same thing but works for an arbitrary image that you pass in as a parameter.

Write the function in the Subprograms module, in week2.scala.

(Note the file name.)

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

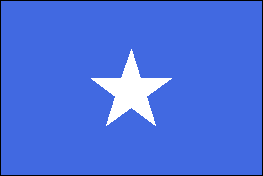

Flag #1: Somalia

Write an effect-free function flagOfSomalia that:

takes as its only parameter the entire flag’s width as a

Double; andreturns a

Picof the national flag of Somalia, whose:width is determined by the parameter;

height is two thirds of the width;

star is four thirteenths of the width of the entire flag; and

colors are

RoyalBlueandWhite.

Place the function in the Subprograms module, in week2.scala. (Note the file name.)

You can use the function star in package o1 to create a five-pointed star. Pass the

star’s width and color as parameters.

Position the star with onto. Here’s a separate example of that method:

val darkCircle = circle(300, Black)darkCircle: Pic = circle-shape show(testPic.onto(darkCircle))

Watch out with integer division when you do the math. Remember this (from Chapter 1.3):

2 / 3res8: Int = 0 2 * 150.0 / 3res9: Double = 100.0

Your function should return the picture, not display it with show. If you want to show

the result, you can combine the two functions like this:

show(flagOfSomalia(400))

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

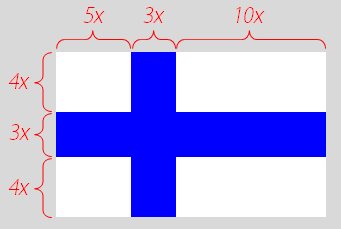

Flag #2: Finland

In the same file, write a function flagOfFinland that:

receives a width as a

Doublejust like the previous function; andreturns an image of the Finnish flag with the given width and the official proportions as per the illustration on the right.

Use the colors White and Blue.

Instructions and hints:

First compute the length denoted by x in the illustration. Use that as a basic unit for computing the other measurements. Create rectangles of the right sizes to serve as the flag’s “pieces”. Position the pieces side by side or one above the other. There’s no need to a scaling method.

Please note that the function’s parameter specifies the width of the entire flag, not the length marked as x in the illustration.

Use local variables.

Remember:

Picobjects are immutable. Their methods generate newPicobjects; they don’t mutate the originalPic.See, for example, the rotating-horse example above.

Don’t make your function

showthe flag. Just return the picture.See if you can solve the assignment both with the help of

ontoand without.

If you see “thin white gaps” in your flag, look here

Depending on your chosen solution, you might see thin “gaps” of white between some of the flag’s blue areas, even though you programmed no such thing. If that happens, just ignore the gaps. They are caused by a limitation in the graphics library that we rely on; that issue will be resolved later. Submit your work as if the gaps weren’t there.

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

Go ahead and make other images as well.

Summary of Key Points

In addition to singleton objects, you can define classes. A class represents the shared characteristics (variables and methods) of objects that resemble each other.

Classes make object-oriented programming more convenient. In object-oriented programs written in Scala, class definitions tend to play a larger part than singleton objects do.

Given a class definition, you can instantiate the class. That is to say, you can create an instance of it, an object. The instance has the characteristics (variables and methods) defined by its class but it has its own instance-specific values stored in the variables.

In Scala, you can instantiate a class with an expression of the form

ClassName(constructorParams).Constructor parameters convey information that is useful for initializing the new object.

Adopting different perspectives, you can view classes as: 1) parts of program code; 2) data types; 3) descriptions of generic concepts in a conceptual model; and 4) useful abstractions.

Objects are manipulated via references.

You can assign an object reference to a variable and then access the object via the variable.

Multiple references may point at the same object from different contexts.

A single (

var) variable may store a reference to one object at one time and a reference to another object at another time.

Links to the glossary: class, data type; instance, to instantiate, constructor parameter; reference; abstraction.

Feedback

Please note that this section must be completed individually. Even if you worked on this chapter with a pair, each of you should submit the form separately.

Credits

Thousands of students have given feedback and so contributed to this ebook’s design. Thank you!

The ebook’s chapters, programming assignments, and weekly bulletins have been written in Finnish and translated into English by Juha Sorva.

The appendices (glossary, Scala reference, FAQ, etc.) are by Juha Sorva unless otherwise specified on the page.

The automatic assessment of the assignments has been developed by: (in alphabetical order) Riku Autio, Nikolas Drosdek, Kaisa Ek, Joonatan Honkamaa, Antti Immonen, Jaakko Kantojärvi, Niklas Kröger, Kalle Laitinen, Teemu Lehtinen, Mikael Lenander, Ilona Ma, Jaakko Nakaza, Strasdosky Otewa, Timi Seppälä, Teemu Sirkiä, Anna Valldeoriola Cardó, and Aleksi Vartiainen.

The illustrations at the top of each chapter, and the similar drawings elsewhere in the ebook, are the work of Christina Lassheikki.

The animations that detail the execution Scala programs have been designed by Juha Sorva and Teemu Sirkiä. Teemu Sirkiä and Riku Autio did the technical implementation, relying on Teemu’s Jsvee and Kelmu toolkits.

The other diagrams and interactive presentations in the ebook are by Juha Sorva.

The O1Library software has been developed by Aleksi Lukkarinen and Juha Sorva. Several of its key components are built upon Aleksi’s SMCL library.

The pedagogy of using O1Library for simple graphical programming (such as Pic) is

inspired by the textbooks How to Design Programs by Flatt, Felleisen, Findler, and

Krishnamurthi and Picturing Programs by Stephen Bloch.

The course platform A+ was originally created at Aalto’s LeTech research group as a student project. The open-source project is now shepherded by the Computer Science department’s edu-tech team and hosted by the department’s IT services. Markku Riekkinen is the current lead developer; dozens of Aalto students and others have also contributed.

The A+ Courses plugin, which supports A+ and O1 in IntelliJ IDEA, is another open-source project. It has been designed and implemented by various students in collaboration with O1’s teachers.

For O1’s current teaching staff, please see Chapter 1.1.

Additional credits appear at the ends of some chapters.

We create a new object with a command that starts with the name of the class that we want to instantiate — that is, the type of the object to be created. In Scala, most classes have names that start with a capital letter.