Luet oppimateriaalin englanninkielistä versiota. Mainitsit kuitenkin taustakyselyssä osaavasi suomea. Siksi suosittelemme, että käytät suomenkielistä versiota, joka on testatumpi ja hieman laajempi ja muutenkin mukava.

Suomenkielinen materiaali kyllä esittelee englanninkielisetkin termit.

Kieli vaihtuu A+:n sivujen yläreunan painikkeesta. Tai tästä: Vaihda suomeksi.

Chapter 2.6: Many Ways to Use a Variable

Variables Grouped in Different Ways

Chapter 1.4 told us: in a computer program, a variable is a named storage location for a single value.

That applies to all the variables that you’ve encountered, but those variables differ from each other in various other ways. Let’s pause for a moment to sort out what we already know.

We can group variables in categories using a variety of criteria.

Grouping by mutability

Scala explicitly classifies variables as either vals or vars (Chapter 1.4). This is

depicted below.

(Many other programming languages either don’t make this distinction or don’t emphasize it as Scala does.)

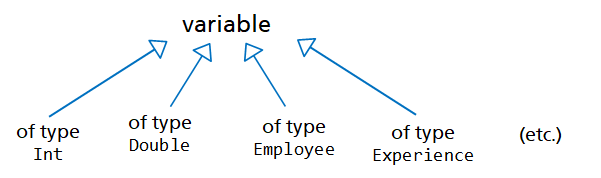

Grouping by data type

Another fairly obvious way to classify variables by their data type:

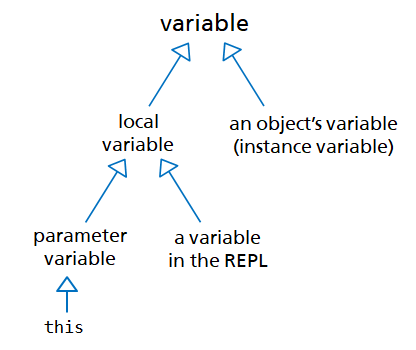

Grouping by context of use

A third classification groups variables by the contexts where they are defined.

Some variables are instance variables defined on objects (Chapter 2.4). Others are local variables of a subprogram; they exist in a frame on the call stack only while the computer is running the subprogram. Parameter variables are a special kind of local variable: instead of being assigned a value directly, they receive their value from a parameter expression in a subprogram call (Chapter 1.7). Variables defined in the REPL can also be considered local variables whose lifetime spans the REPL session.

Roles of Variables

We can also group variables by the way we use them, their roles. Although we haven’t paid any particular attention to this so far, you have already seen variables being used in a few different roles.

In Chapter 2.2, our account object had a couple of variables that we used in different

ways. The account’s number variable never changed its value. In contrast, balance’s

value changed whenever we deposited or withdrew money; more specifically, we used the

variable’s old value and the size of the adjustment to determine new values for the

variable. Clearly, this variable had a different part to play in the program than the

account number.

The role of a variable (muuttujan rooli) characterizes how you use the variable in a program: when and why its value changes, if it changes at all. Research suggests that it’s possible to describe most variables in computer programs aptly with a dozen or so role labels. Eight role names are enough to label nearly all the variables in O1’s example programs.

For example, we can say that the account’s balance variable has a role of “gatherer”:

at any given time, its current value has been obtained by gathering and combining the

effects of earlier operations — in this case, by summing deposits and withdrawals.

In this ebook, we’ll use roles of variables as an aid for designing programs. Many of the example programs have variables annotated with role labels as shown below:

var balance = 0.0 // gatherer

A variable’s role doesn’t express everything that one can do with it. If we had

wanted to, we could have assigned any number we pleased to balance. The role describes

how the variable is actually used in the program. It has significance to the human

programmer, not the computer.

You’ve already seen a examples of a few roles. Let’s discuss each one in turn.

Fixed values

A fixed value is set in stone.

The simplest role is the fixed value (kiintoarvo). Once a fixed-valued variable

has been initialized, it’s never changed. In Scala, fixed values are practically always

vals.

A fixed-valued instance variable describes a permanent attribute of an object (such as the account number).

As for fixed-valued local variables, parameters are the most common example. For example,

the multiplier parameter of method monthlyCost in class Employee is a fixed value

whose value remains unchanged thoughout the entire method call:

def monthlyCost(multiplier: Double) = this.monthlySalary * this.workingTime * multiplier

Constants

Fixed-valued variables whose value is already known before the program runs are often called constants (vakio). A programmer may define a constant to represent a universal fact, such as an approximate value of π, or an application-specific fact known ahead of time.

val Pi = 3.141592653589793

val MinimumAge = 18

val DefaultGreeting = "Hello!"

A constant doesn’t need to be a number. It can store any type of immutable information.

Constants are a good tool for making programs easier to read. A constant’s name communicates the programmer’s intent better than a “magic number” — which is programmer-speak for a literal whose purpose is undocumented.

Constants can also make code easier to modify, too. If we decide to exchange the value of a constant as our program evolves, we can do that with a single change to the constant definition, even if the value is used in various places throughout our program (or even across multiple programs). Magic numbers, in contrast, create implicit dependencies between parts of code: if we change one number, we may easily forget to make the corresponding changes elsewhere. Such implicit coupling often leads to bugs.

Many software libraries define constants. For example, the package scala.math provides

a fixed-valued variable Pi that stores an approximation of π. The colors that you’ve

used from package o1 (such as Red, Blue, and CornflowerBlue) are also constants,

each referring to a single object of type Color.

Temporaries

OK, so this illustration works only in the Finnish edition of the ebook. In Finnish, if you put information “behind your ear”, it means you store it until you need it. Oh, well. Now you can (temporarily?) recall a Finnish idiom.

You already worked with temporaries (tilapäissäilö) in Chapters 1.8 and 2.2.

These variables do a “temp job” of storing a value for later use by the algorithm in which

they appear. For example, in the account’s withdraw method, you stored the withdrawn sum

temporarily, while adjusting the balance, before returning the temporary’s value:

def withdraw(sum: Int) =

val withdrawn = min(sum, this.balance) // withdrawn is a temporary

this.balance = this.balance - withdrawn

withdrawn

A similar use for a temporary is to store an intermediate result during a sequence of arithmetic operations. Temporaries are typically local variables.

The value of most temporaries never changes once set; in Scala programs, almost all

temporaries are vals. Whether you describe a variable as a fixed value or a temporary

is largely a matter of taste.

Gatherers

A gatherer (kokooja) is a variable whose new value is computed by combining the gatherer’s previous value with new data. Depending on the program, the new data could be user input, a method parameter, or something else.

Here are a few examples of instance variables that serve as gatherers:

The balance of an account (already discussed above). The command

this.balance = this.balance - withdrawnis typical of a gatherer: it computes the new balance from the old balance and another value.A monster’s current health (in Chapter 2.4), which worked much like an account’s balance.

The location of a playable character in a game that determines the character’s current location based on 1) where the character was previously; and 2) the direction the player instructed the character to move in.

The code might look something like this:

this.location = this.location.neighbor(directionOfMove). Here, the character object is associated with a location object. It asks the location to find the neighboring location in the specified direction and updates its own location accordingly.We’ll do something similar later in this chapter.

You can think of a gatherer as a variable that receives additional pieces of information so that its value at any given time depends on everything it has received so far.

Gatherers are common not just as instance variables but as local variables, too. We’ll first see an example of a local gatherer in Chapter 5.5.

Most-recent holders

We can assign a new value to the name of an Employee:

val testEmployee = Employee("Reginald Dwight", 1916, 12345)testEmployee: o1.classes.Employee = o1.classes.Employee@1100b25

testEmployee.nameres0: String = Reginald Dwight

testEmployee.name = "Elton John"testEmployee.name: String = Elton John

The variable name keeps track of the latest name assigned to the employee. The latest

name simply replaces the earlier value; the old value is not used for computing the new

one, unlike with gatherers. We say that a variable such as name, which stores the latest

value of a particular kind, is a most-recent holder (tuoreimman säilyttäjä).

name is typical example of a most-recent-holding instance variable: it stores an object

attribute whose value can be replaced with a new one. Most-recent holders are also useful

as local variables, which we’ll explore in Chapter 5.5.

A most-recent holder discards its earlier values.

How to benefit from roles

Role names describe how we programmers typically use variables. We can use them for thinking about the programs that we write and read. Knowing a variable’s role gives insight into the behavior of the program you’re working on.

Each role corresponds to the abstract solution of a small subproblem that occurs time and time again in a wide range of contexts. Role labels capture common patterns of variable use that experienced programmers recognize in programs that seem otherwise unrelated.

You, as an O1 student, aren’t required to label your variables with roles. However, you may find them helpful as you sketch out solutions to programming problems; many beginner programmers have. One of the challenges of learning to program is recognizing recurring subproblems in programs that seem different on the surface, so that you can apply a known solution. This is where roles can help: they hint at how you can solve certain subproblems that you’ll run into repeatedly as you program.

Use roles as a tool for thinking:

“Hmm... I’m supposed to produce the sum of all the scientific measurements that I receive as inputs... I could use a gatherer to keep track of the total as it builds up. Each time I process a new measurement, I’ll add it to the gatherer’s old value.”

When you write programs, consider each variable’s data type and role. When you read programs, notice the different roles that variables play. And when you document a program, you might be able to help the reader by annotating roles in code as comments.

On roles and design patterns

Variable roles are one way to label solution patterns to recurring programming needs. They apply to individual variables, small but important components of an entire program.

Programmers have also come up with descriptions of larger-scale patterns. The best-known work in this vein is known as design patterns (suunnittelumalli). Each design pattern captures a recurring problem in program design and suggests a solution to it on a general level, typically involving one or more classes. Design patterns will be discussed further in CS-C2120 Programming Studio 2.

More roles

Soon, in Chapter 3.1, you’ll encounter another role, the stepper. A bit later, we’ll discuss containers (Chapter 4.1), most-wanted holders (Chapter 4.1), and flags (Chapter 5.6).

Interconnected Objects

Our earlier examples have shown that you can think of an object-oriented program’s behavior as communication between objects. For that communication to work, we need to connect objects to each other.

A course object, for example, might refer to a room object that represents the classroom

where the course is taught; it might also refer to a number of other objects that

represent the enrolled students. Similarly, in the GoodStuff application, a Category

object is linked to the experiences in that category, one of which is the diarist’s

favorite. And an object that represents a character in a game might store a reference

to a Pos object that represents the character’s current location.

In earlier chapters, you learned to define a type as a class. What we haven’t done yet is write a class that refers to another custom class that we wrote. Which is what we’ll do now.

As a first step, we’ll examine an example whose two classes represent — in greatly simplified fashion! — the orders and customers of an imaginary online store. After that, you’ll get to apply what you learned by defining an object-oriented model for a game.

Our goal: classes to represent customers and orders

To create a customer object, we provide a name, a customer number, an email address, and a street address as constructor parameters:

val testCustomer = Customer("T. Tester", 12345, "test@test.fi", "Testitie 1, 00100 Testaamo, Finland")testCustomer: o1.classes.Customer = o1.classes.Customer@a7de1d

Calling description gives us a textual summary of key information:

println(testCustomer.description)#12345 T. Tester <test@test.fi>

To create an order, we specify an order ID number and a customer. The latter parameter is

a reference to a Customer object:

val exampleOrder = Order(10001, testCustomer)exampleOrder: o1.classes.Order = o1.classes.Order@18c6974

The order we created above starts out empty, but we can call addProduct to add items.

In this toy example, we don’t concern ourselves with any product details. Instead, we just

indicate each product’s price per unit and the number of units that are being bought. In

the REPL session below, we place an order for 100 items priced at 10.5 euros each, plus a

single 500-euro product.

exampleOrder.addProduct(10.5, 100)exampleOrder.addProduct(500.0, 1)

Order objects, too, have a description:

println(exampleOrder.description)order 10001, ordered by #12345 T. Tester <test@test.fi>, total 1550.0 euro

The ordering customer’s description is a substring of the order’s description.

We can also ask an order object to tell us who placed the order, which gives us a reference to that customer object:

exampleOrder.ordererres1: Customer = o1.classes.Customer@a7de1d

Crucially, what we got is a reference of type Customer — not a string, for example.

This means that we managed to use the order object to access another object associated

with it. We can use that other object just like any other, as in this chain of requests:

exampleOrder.orderer.addressres2: String = Testitie 1, 00100 Testaamo, Finland

Here’s what’s happening: the variable exampleOrder contains a reference to an order

object; that order object’s orderer variable contains a reference to a customer object;

and the customer object’s address variable contains a reference to a string.

Implementing the two classes

Here’s the customer class. There isn’t anything particularly new about it:

class Customer(val name: String, val customerNumber: Int, val email: String, val address: String):

def description = "#" + this.customerNumber + " " + this.name + " <" + this.email + ">"

Each customer object has a few fixed values as instance variables. It uses them to store its attributes.

Now to the other class. Let’s first sketch it out as pseudocode:

class Order(fixed values: a number and a customer who placed the order): let’s use a gatherer to keep track of the total price, which starts at zero def addProduct(pricePerUnit: Double, numberOfUnits: Int) = multiply the parameters and add the result to the gatherer def description = return a string description of the order, requesting the customer info from the customer object associated with this order end Order

An order object must keep track how each addition to the order affects the order’s total price. We do this by using an instance variable as a gatherer.

We’re working with a model that consists of objects of different classes. We need each order object to store a reference to a customer object.

Via the stored reference, we can consult the relevant customer object as we form a description of the order.

This pseudocode translates directly to actual program code, since it’s perfectly okay to

use the other class we wrote, Customer, in our definition of Order:

class Order(val number: Int, val orderer: Customer):

var totalPrice = 0.0

def addProduct(pricePerUnit: Double, numberOfUnits: Int) =

this.totalPrice = this.totalPrice + pricePerUnit * numberOfUnits

def description = "order " + this.number + ", " +

"ordered by " + this.orderer.description + ", " +

"total " + this.totalPrice + " euro"

end Order

We use the Customer class as the type for one of Order’s

constructor parameters. This means that when creating an

Order instance, we need to pass in a reference to a Customer

instance. We add the word val so that the reference also

gets stored in an instance variable.

this.orderer evaluates to a reference that points to a customer

object. We can call its method by writing this.orderer.description:

the order object commands the customer object to produce its

description, receives a string as a response, and uses that string

as part of its own description.

That’s all it took to define a link from the Order class to the Customer class —

and, by extension, from each order object to one customer object. These relationships

between objects are depicted in the diagram below.

Assignment: more toString methods

As an optional mini-assignment, modify the given classes Customer

and Order so that instead of a description method, they have

a toString-method (Chapter 2.5). You’ll find the classes in

the IntroOOP module.

Note that once toString is defined on customers, you don’t need

to explicitly invoke it in the toString of class Order. It

suffices to concatenate a string with a reference to a customer

object.

If you want more practice, try modifying the description method

of Orders to use string interpolation (s and dollar signs)

instead of plus operators.

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

How about linking to many objects?

What if we want each course object to store references to multiple enrolled students, or each category to refer to multiple experiences? Or, perhaps, record in each customer object a list of all the orders that customer has placed?

We won’t tackle this question in earnest until Chapter 4.1. But here’s the short of it: We’ll store the students, experiences, or orders as the elements of a collection (such as a buffer). We’ll then link that collection to the course, category, or customer object.

More Examples

Example: Guarded treasures

In Chapter 2.4, we worked on a Monster class. Here’s a working version (with

a toString method instead of description):

class Monster(val kind: String, val healthMax: Int):

var healthNow = healthMax

override def toString = this.kind + " (" + this.healthNow + "/" + this.healthMax + ")"

def sufferDamage(healthLost: Int) =

this.healthNow = this.healthNow - healthLost

end Monster

We’re not going to build a full game around this example, but let’s extend the theme by adding another toy class.

Let’s say our imaginary game features hoards of treasure, each guarded by a troll —

each Treasure object is associated with a Monster object that is the treasure’s

guardian. Here’s a usage example:

val hoard = Treasure(1000.0, 50)hoard: Treasure = Treasure (worth 1000.0) guarded by troll (50/50) hoard.valueres3: Double = 1000.0 hoard.guardianres4: Monster = troll (50/50) hoard.appealres5: Double = 20.0

Each treasure has a value represented by a Double.

Moreover, each treasure has a challenge level, which

is also a number.

A higher challenge level means that the treasure is guarded by a stronger troll.

We can ask a Treasure object to provide its value

and its guardian.

A Treasure is further characterized by its appeal:

the treasure’s value divided by its guardian’s current

health score. This means that a treasure’s appeal will

go up as its guardian’s health goes down. In this example,

we have a treasure guarded by 50-health troll at full

strength, so the treasure’s appeal is 1000.0/50 or 20.0.

Here’s an implementation for class Treasure.

class Treasure(val value: Double, val challenge: Int):

def guardian = Monster("troll", this.challenge)

def appeal = this.value / this.guardian.healthNow

override def toString = "treasure (worth " + this.value + ") guarded by " + this.guardian

end Treasure

We use the guardian’s current health as we determine the treasure’s appeal.

Example: Bosses of bosses

Example: Celestial bodies

Below is an additional example where we use one class in the definition of another and

thus link together objects of different types. We recommend that you study this example

especially if you are unsure whether you understood the Order and Treasure examples

above, or if you find yourself struggling with the game-themed assigment below. You won’t

miss any novel content by skipping this example, though.

The classes CelestialBody and AreaInSpace

Just for practice, let’s define a couple of toy classes and create a two-dimensional model of Earth and its moon in space.

The plan is for instances of class CelestialBody to represent

individual planets or satellites. We’ll also have an AreaInSpace

class: an instance of that class represents a section of space

that contains the Earth and the Moon. An AreaInSpace object will

be associated with exactly two CelestialBody objects. This

idea is similar to how we associated each Order object with

one Customer and each Treasure object with one Monster.

Here’s class CelestialBody:

class CelestialBody(val name: String, val radius: Double, var location: Pos):

def diameter = this.radius * 2

override def toString = this.name

end CelestialBody

Celestial bodies have names, radiuses, and locations.

The location is a Pos object: each CelestialBody

object stores a reference to a Pos, which in turn

stores an x and a y.

Here’s the AreaInSpace class, which makes use of CelestialBody:

class AreaInSpace(size: Int):

val width = size * 2

val height = size

val earth = CelestialBody("The Earth", 15.9, Pos(10, this.height / 2))

val moon = CelestialBody("The Moon", 4.3, Pos(971, this.height / 2))

override def toString = s"${this.width}-by-${this.height} area in space"

end AreaInSpace

When an AreaInSpace object is created, it receives a constructor

parameter that indicates its size (in coordinate units). In this

toy example, let’s say that any AreaOfSpace we create is always

twice as wide as it is high. We’ll store these dimensions in the

object’s instance variables.

Every instance of AreaInSpace is also associated with two

CelestialBody objects. In this simple program, we’ll give those

two objects specific names, radiuses, and locations, which we spell

out in the code.

With the classes so defined, we can use them in the REPL:

val space = AreaInSpace(500)space: AreaInSpace = 1000-by-500 section of space space.earthres6: CelestialBody = The Earth space.moonres7: CelestialBody = The Moon

We create an AreaInSpace. As we do so...

... we also get two CelestialBody objects, which the

AreaInSpace object’s instance variables earth and moon

refer to.

We can then access those objects’ methods and variables:

space.earth.diameterres8: Double = 31.8 space.earth.locationres9: o1.Pos = (10.0,250.0) space.moon.locationres10: o1.Pos = (971.0,250.0) space.moon.radiusres11: Double = 4.3 space.moon.location.xDiff(space.earth.location)res12: Double = -961.0

The AreaInSpace has two celestial bodies that

we access through the corresponding variables.

Each of the CelestialBody objects has a Pos

object that we access through the object’s location

variable.

In the next Chapter 2.7, there’s another optional example that continues from this one: we’ll build a graphical view of space using these classes as the domain model.

A Game Project

Let’s start working on a new module. You’ll build it incrementally across several chapters, in parallel with other modules such as Odds. By the time we finish with this module, you’ll have programmed a playable game.

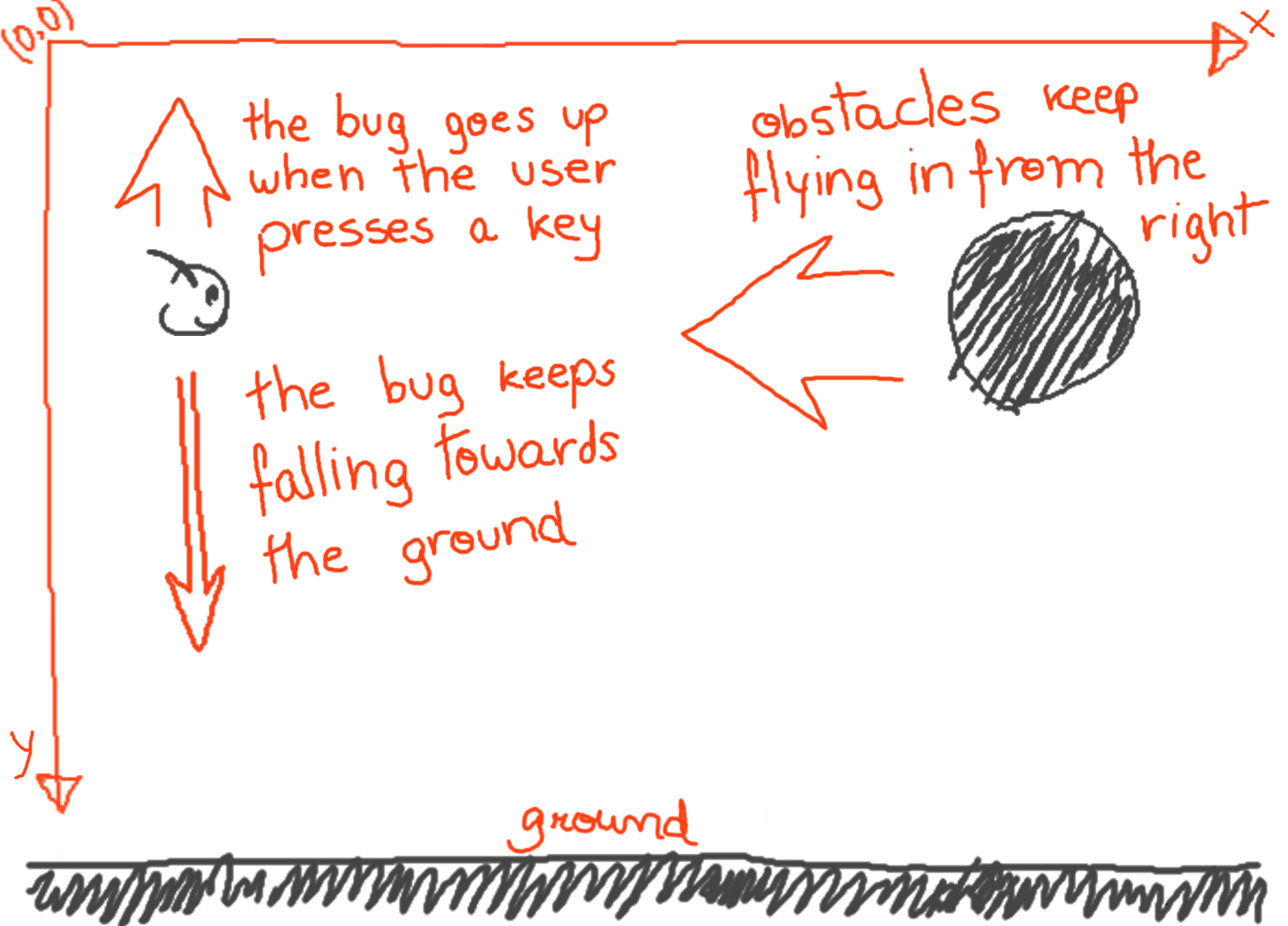

FlappyBug

The goal is to create a game where the player controls a ladybug and tries to avoid obstacles. The ladybug makes a quick upward movement whenever the player commands it to flap its wings. Otherwise, the bug constantly sinks downwards, so the player has to keep flapping to keep it airborne. The bug moves only vertically; obstacles fly in horizontally from the right.

In this chapter, we’ll create a model of the program’s domain. That is, we’ll model the concepts of the game world (such as obstacle) and the operations associated with them (such as flying). We won’t build a user interface for the game just yet.

We’ll begin with an initial version of the game that features one bug and only one obstacle. In later chapters, you’ll expand on this initial domain model and create a graphical user interface for the program.

Let’s now program three classes:

Bug: defines the concept of a bug and the attributes and methods associated with it.Obstacle: defines the concept of an obstacle.Game: An instance of this class corresponds to a single game session and keeps track of the game’s overall state. Via aGameobject, we can access the parts of the game world (the bug and one obstacle). The game object determines how and when to activate the methods of those other objects as the game progresses.

An implementation for Obstacle is provided as an example below. After studying it, you

get to write classes Bug and Game yourself.

Class Obstacle

When we create an obstacle, we specify its size (radius) and initial position within the game world’s two-dimensional coordinate system. Like this, for instance:

val bigObstacle = Obstacle(150, Pos(800, 200))bigObstacle: o1.flappy.Obstacle = center at (800.0,200.0), radius 150

In this early version of the game, an obstacle isn’t capable of much anything, but it does know how to fly:

bigObstacle.approach()bigObstacleres13: o1.flappy.Obstacle = center at (790.0,200.0), radius 150 bigObstacle.approach()bigObstacle.approach()bigObstacleres14: o1.flappy.Obstacle = center at (770.0,200.0), radius 150

An Obstacle object has a mutable state that changes

when we call approach on the object. Each invocation

of the method reduces the obstacle’s x coordinate by ten.

Here’s a pseudocode sketch of the class’s implementation:

class Obstacle(a fixed value to store the radius; a gatherer to store the position):

def approach() =

Adjust the gatherer that keeps track of my current position:

determine the new value from the old one by adding -10 to the x coordinate.

override def toString = combine the obstacle’s data into a description like the one in the example

end Obstacle

The same in Scala:

class Obstacle(val radius: Int, var pos: Pos):

def approach() =

this.pos = this.pos.addX(-10)

override def toString = "center at " + this.pos + ", radius " + this.radius

end Obstacle

Before we move on to Bug and Game, there are two noteworthy things to discuss

here:

One of the methods uses the magic number 10 that controls the speed of obstacles.

There is an empty pair of round brackets in approach’s definition

Why is that? On a related note, perhaps you already wondered why we

used a similar pair of brackets earlier when calling approach in

the REPL.

A constant is better than magic

To avoid using a magic number, we can define a constant:

val ObstacleSpeed = 10

But where to write this definition? The approach that we’ll adopt here is to reserve a separate location for the various constants that affect the rules of the FlappyBug game.

You can find a partial implementation of the game in the FlappyBug module. The file

constants.scala contains the above definition of ObstacleSpeed. The obstacle class

is defined in another file, Obstacle.scala; its method approach uses the constant as

shown below.

class Obstacle(val radius: Int, var pos: Pos):

def approach() =

this.pos = this.pos.addX(-ObstacleSpeed)

override def toString = "center at " + this.pos + ", radius " + this.radius

end Obstacle

We can now use the named constant instead of a magic number.

Interlude: Parameterless, Effectful Methods — And Brackets

The empty brackets are there because the method takes no parameters: it has an empty

parameter list. On the other hand, it’s true that we have created other parameterless

methods without empty brackets; these include toString and description, above, and

many others.

There is a convention among Scala programmers to provide a visual hint about whether

a parameterless method is effectful or effect-free. When a parameterless method is

effectful (as approach is), we mark this with an empty pair of round brackets in

the method’s definition. If a parameterless method is effect-free (like toString or

description), we leave out the brackets.

We also either include or omit the empty brackets when we call a parameterless method.

In bigObstacle.approach(), the brackets emphasize that this method call impacts on

obstacle object’s state.

Conversely, the expression testCustomer.description does not betray whether it calls

a method named description or accesses a variable of that name. Scala’s designers have

deliberately made calling an effect-free, parameterless method look the same as accessing

the value of an instance variable (which also doesn’t have an effect on state). There are

reasons why this is a good idea; the easiest to appreciate at this stage is convenience:

the class’s user doesn’t need to recall or care whether, say, description is an instance

variable or a method.

Follow these conventions

You will need to observe the above conventions on the use of brackets. When a programming assignment in O1 specifies that you should write a method that has empty brackets as its parameter list, make sure you do, and also include the brackets when calling that method.

FlappyBug, Part 1 of 17: Class Bug

How a Bug should work

A bug object is created like this:

val myBug = Bug(Pos(300, 200))myBug: o1.flappy.Bug = center at (300.0,200.0), radius 15

As you can see in the text that toString produced, bugs are similar to obstacles in

that they have a location and a radius. We can also examine these two attributes separately:

myBug.posres15: o1.Pos = (300.0,200.0) myBug.radiusres16: Int = 15

A newly created bug is initially located at the Pos that we

specified with the constructor parameter.

At least in this version of our program, any bug always has an unchanging radius of 15.

A bug has a method for “flapping its wings”. For now, we’ll model the flight of the bug by simply reducing the bug’s y coordinate by whichever amount was given as a parameter.

myBug.flap(9.5)myBug.posres17: o1.Pos = (300.0,190.5) myBug.flap(20.5)myBug.posres18: o1.Pos = (300.0,170.0)

A bug is also capable of falling downwards. The fall method increases the bug’s

y coordinate by two:

myBug.fall()myBug.posres19: o1.Pos = (300.0,172.0) myBug.fall()myBug.posres20: o1.Pos = (300.0,174.0)

Task description

Implement class Bug in Bug.scala in the FlappyBug module. It must work as described

above.

Instructions and hints

Please use the specified names:

pos,flap, etc. This guideline applies to all the other programming assignments in O1 that ask you to implement a class according to specification.The bug’s position changes; let’s model this with a

var. The radius doesn’t change; use aval.fallandflapare methods, sodefis appropriate.

The class you’ll write is in many ways similar to the obstacle class that we already created.

The

fallmethod is effectful and takes no parameters. Apply what you just learned about empty brackets in Scala.You can use the constants defined in

constants.scalain favor of magic numbers.To match the REPL output shown above, you’ll also need to write a

toStringmethod for your class.When you test your program, make sure you load the FlappyBug module in the REPL.

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

FlappyBug, Part 2 of 17: Class Game

An object of type Game represents the overall state of a FlappyBug game. In this

version of the game, such a state comprises a single bug and a single obstacle. A Game

object also provides methods for modifying this state: for example, when time passes,

it directs the bug to fall and the obstacle to advance. To that end, the Game object

stores references that point to the other objects that it commands.

How a Game should work

We don’t need constructor parameters to instantiate class Game:

val testGame = Game()testGame: o1.flappy.Game = o1.flappy.Game@10eb1721

To instantiate a class that doesn’t take any constructor parameters, write an empty pair of brackets after the class name.

A newly created Game object represents the game’s initial state, which is always this:

there’s a ladybug at (100,40) and an obstacle with a radius of 70 at (1000,100).

The game object has instance variables named bug and obstacle, which are vals. They

refer to the bug and obstacle objects that are part of that game session:

testGame.bugres21: o1.flappy.Bug = center at (100.0,40.0), radius 15 testGame.obstacleres22: o1.flappy.Obstacle = center at (1000.0,100.0), radius 70

Calling the parameterless method timePasses advances the game’s state

by making the bug fall and the obstacle approach from the right:

testGame.timePasses()testGame.bugres23: o1.flappy.Bug = center at (100.0,42.0), radius 15 testGame.obstacleres24: o1.flappy.Obstacle = center at (990.0,100.0), radius 70

We observe that there’s a change in the coordinates of the bug and

the obstacle that are associated with this Game instance.

A Game object also has the method activateBug, which we intend to call

in response to the human player pressing keys on the keyboard. When activateBug

is invoked on a Game object, it instructs the bug to flap its wings with a

“strength” of 15:

testGame.activateBug()testGame.bugres25: o1.flappy.Bug = center at (100.0,27.0), radius 15

The bug’s y coordinate is now 15 units less than it was.

Task description

Implement class Game in Game.scala.

Instructions and hints

The class doesn’t take any constructor parameters, so you can place the colon right after

class Game. This has already been done for you in the skeleton code provided inGame.scala.

Define two instance variables (named

bugandobstacle) and two methods (activateBugandtimePasses).Remember that even though classes have upper-case names (like

Bug), those variables should start with a lower-case letter, as inbug.

Make the instance variables refer to

BugandObstacleobjects. Make sure you create instances of those classes.To clarify: do not copy the code of class

Bugor classObstacleinto classGame. Instead, use those other classes from withinGame: create one instance of each of the two classes.You may create an object where you define an instance variable:

val variable = ClassName(parameters)If this part feels unclear, you may wish to revisit the optional

AreaInSpaceexample above.

When implementing

activateBugandtimePasses, don’t re-implement the functionality that’s already available in classesObstacleandBug. (In particular: don’t do any arithmetic on coordinates!) Instead call the appropriate methods on the bug and the obstacle.Again, use empty brackets when you define or call effectful methods that take no parameters.

You can use the constants defined in

constants.scala. You may also wish to define additional constants there and use them.If you feel unsure how we can use this class as a part of an actual graphical game, don’t worry. Our game still lacks a user interface, but we’ll address that soon.

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

Summary of Key Points

You can consider variables from multiple angles: Is it a

valor avar? What is its data type? Is it a local variable or an instance variable? What is the variable’s role in the program?The majority of variables can be usefully described using one of a dozen or so role labels.

A fixed value can be used (among other things) for storing the immutable attribute of an object; a gatherer for accumulating a result by combining multiple inputs; a temporary for storing an intermediate result for a while; and a most-recent holder for keeping track of an attribute whose value may be replaced by another.

Fixed-valued variables whose value is known before running the program are commonly known as constants.

Constants make code easier to understand and modify.

In Scala, it’s customary to capitalize the names of constants.

You can define instance variables whose type is a custom class that you wrote yourself. This establishes links between classes.

If a class defines such an instance variable, each object of that type (e.g., each order) stores a reference to another object (e.g., a customer).

Scala has certain rules and conventions for using round brackets in parameterless methods. Careful!

Links to the glossary: variable, role, fixed value, temporary, gatherer, most-recent holder; constant, magic number; reference; model.

Feedback

Please note that this section must be completed individually. Even if you worked on this chapter with a pair, each of you should submit the form separately.

Credits

Thousands of students have given feedback and so contributed to this ebook’s design. Thank you!

The ebook’s chapters, programming assignments, and weekly bulletins have been written in Finnish and translated into English by Juha Sorva.

The appendices (glossary, Scala reference, FAQ, etc.) are by Juha Sorva unless otherwise specified on the page.

The auto-grading of the assignments has been developed by the following Aalto students (in alphabetical order): Riku Autio, Kai Bukharenko, Nikolas Drosdek, Kaisa Ek, Rasmus Fyhrqvist, Joonatan Honkamaa, Antti Immonen, Jaakko Kantojärvi, Onni Komulainen, Niklas Kröger, Kalle Laitinen, Teemu Lehtinen, Mikael Lenander, Ilona Ma, Jaakko Nakaza, Strasdosky Otewa, Kaappo Raivio, Timi Seppälä, Teemu Sirkiä, Onni Tammi, Joel Toppinen, Anna Valldeoriola Cardó, and Aleksi Vartiainen.

The illustrations at the top of each chapter and the similar drawings elsewhere in the ebook are the work of Christina Lassheikki.

The animations that detail the execution Scala programs have been designed by Juha Sorva and Teemu Sirkiä. Teemu Sirkiä and Riku Autio did the technical implementation, relying on Teemu’s Jsvee and Kelmu toolkits.

The other diagrams and interactive presentations in the ebook are by Juha Sorva.

The O1Library software has been developed by Aleksi Lukkarinen, Juha Sorva, and Jaakko Nakaza. Several of its key components are built upon Aleksi’s SMCL library.

The pedagogy of using O1Library for simple graphical programming (such as Pic) is

inspired by the textbooks How to Design Programs by Flatt, Felleisen, Findler, and

Krishnamurthi and Picturing Programs by Stephen Bloch.

The course platform A+ was originally created at Aalto’s LeTech research group as a student project. The open-source project is now shepherded by the Computer Science department’s IT services; the project has received contributions from dozens of Aalto students and others.

The A+ Courses plugin, which supports A+ and O1 in IntelliJ IDEA, is another open-source project. It has been designed and implemented by various students in collaboration with O1’s teachers.

For O1’s current teaching staff, see Chapter 1.1.

Additional credits for this page

The FlappyBug game is inspired by the work of Dong Nguyen.

In Scala, it’s customary to capitalize the names of constants (as O1’s style guide will also tell you).