Luet oppimateriaalin englanninkielistä versiota. Mainitsit kuitenkin taustakyselyssä osaavasi suomea. Siksi suosittelemme, että käytät suomenkielistä versiota, joka on testatumpi ja hieman laajempi ja muutenkin mukava.

Suomenkielinen materiaali kyllä esittelee englanninkielisetkin termit.

Kieli vaihtuu A+:n sivujen yläreunan painikkeesta. Tai tästä: Vaihda suomeksi.

Chapter 1.7: Creating Custom Functions

Introduction

In this chapter, we’ll revisit some of the functions we’ve already discussed and introduce some new ones. What’s new this time is that we’ll be taking a look at the program code that implements the functions.

To experiment with these functions, start up your REPL as you did in the previous chapter: make sure you have the Subprograms module selected in the Project view as you hit Ctrl+Shift+D. (Alternatively, you can open a code file from the Subprograms module in the editor and then launch the REPL.)

The program code for the chapter is available in o1/subprograms/examples_ch17.scala within

the module, if you’d like to take a look.

Defining a Function

The average function is familiar from Chapter 1.6. We can use it in the REPL as

shown here:

average(2.0, 5.5)res0: Double = 3.75

For that command to work, the averaging function needs a definition. This example function’s definition is fairly simple but still introduces a number of important concepts.

In plain English, what the function does is this: “When the average function is

called, it produces a return value by adding the value of the first parameter to the

value of the second parameter and dividing the sum by two.” This idea is captured

in Scala below.

def average(first: Double, second: Double) = (first + second) / 2

We state: “When you call the average function, you must pass

two Double values as parameters.” More generally, this is where

we define the function’s parameter variables (parametrimuuttuja;

also known as formal parameters) and their data types.

Each parameter variable has a name. In our example, we’ve chosen

simply to call the first parameter variable first and the second

second.

Note the equals sign, which is followed by...

... the actual implementation of the function, known as the function body (funktion runko). The function body implements the algorithm that carries out the intended task. In this example, the body is just a single arithmetic expression that tells the computer how to compute the return value.

The parameter variables first and second genuinely are variables — val variables,

to be more specific, even though it doesn’t say val in front of them. Parameter variables

don’t receive their values from assignment commands but indirectly, via function calls.

Apart from that, though, you can use them just like any other val that you’ve seen.

Function Execution and the Call Stack

The following animation shows another diagram of data in computer memory. The diagram evolves step by step as the program runs. This time, we’ll also inspect what happens within a function: you’ll see how parameter variables work, for instance.

Examine this animation thoroughly! It introduces concepts that are crucial to the programs that we’re about to write.

The piece of code shown in the animation doesn’t accomplish anything much. It just calls the averaging function a couple of times.

The animation introduced frames (kehys). The frames formed a call stack (kutsupino), which is often known simply as the stack. The call stack indeed works much like a real-world stack of items: when a function call begins, a new frame is added to the top of the stack, and when a call terminates by returning a value, that topmost frame is removed from the stack.

The computer uses the call-stack frames to keep track of which function calls are active and what data is associated with each of those calls. At any given time, it’s only the topmost frame of the stack that is active, while the lower frames (of which there was just one in this animation) wait for the frame above to finish its task before resuming theirs.

Hopefully, the animation already helped you make sense of how a function call unfolds. In any case, the significance of the call stack and its frames will soon be highlighted as we take on some more complex functions.

A function call... is what exactly?

Chapter 1.2 mentioned that the word “program” refers both to static program code (as in “The program has 100 lines.”) but to the dynamic processes that take place when a program runs (as in “The program stored the information that the user typed in.”).

“Function call” is similarly ambiguous. Sometimes we mean an expression written in code: “The function call on line 15 has a punctuation error.” And sometimes we refer to processes like the one in the animation above, which take place when a function is executed: “The function call is over and yielded a return value of 4.”

Be wise to both meanings as you go through this ebook and other resources on programming.

Practice Defining a Function

Programming Exercise: meters

Task description

In the United Kingdom and some of its former colonies, feet and inches are still widely used for measuring length. One inch equals 2.54 cm, and one foot is 12 inches. Measurements are commonly expressed as a combination of these units. For instance, a person who is about 180 cm tall might be described as “five foot eleven”: five feet plus eleven inches.

Implement an effect-free Scala function that:

is called

toMeters;takes in, as its first parameter, a number of feet represented as a value of type

Double;similarly takes in a number of inches as its second parameter; and

computes and returns a

Doubleequal to the total length in meters of the given feet and inches (e.g., given the values 5 and 11, returns 1.8034).

Proceed in the following stages: set up the assignment, write some code, test. Keep adjusting and testing your program until it works.

There are some additional instructions for each stage below.

Setup

In IntelliJ, find the Subprograms module and open the file o1/subprograms/week1.scala.

Near the top of the file, there is a comment indicating where to write your code for

this chapter.

Writing your function

First, make sure you understand precisely what the function is supposed to do! This sounds self-evident, sure, but it’s easy to forget. You can lay substantial pain on yourself by overlooking something simple in the task description.

Write the function definition in the indicated section of the file. In this case, one line is enough.

Start with

defand the name of the function.Type in the parameter definitions. Choose sensible names for the parameter variables.

Write the function body. A single arithmetic expression is enough to convert between the units. (Don’t print out the resulting value. Just return it!)

Error messages in IntelliJ

As you edit your code, you’ll see some zigzag underlines

and other annotations in red. Some of your

code may also turn red. This is IntelliJ’s way of letting you

know that it has spotted problems.

and other annotations in red. Some of your

code may also turn red. This is IntelliJ’s way of letting you

know that it has spotted problems.Don’t be flustered if your program lights up in red as soon as you start writing. IntelliJ adjusts these annotations constantly as you type, and incomplete code often prompts a complaint. For instance, when you’ve typed just the word

defand a name, IntelliJ will cry out because the function definition is incomplete.The red highlights can be a great help. You should take them seriously, but only if they remain after you consider your

toMetersfunction to be ready.You can view more detailed error messages by hovering your mouse cursor over the red highlights. Unfortunately, it can be hard to understand what each error message means if you’re going by just what we’ve covered in O1 so far; at this stage, you may find it easier to fix your code by comparing it to the ebook’s examples.

Take care that no red error annotations remain. In particular, eliminate any errors in punctuation. Did you use at least round brackets, a comma, and an equals sign? Were you consistent in how you wrote the name of each variable?

Compiling your code

Before the computer can run your Scala code (in the REPL or otherwise), it needs to compile (kääntää) the code into a form that it can execute. As part of the compilation process, the computer also thoroughly checks that your code follows the rules of the programming language. That check may produce errors that you need to fix before your code can run.

IntelliJ compiles your code automatically whenever you launch a program for the first time or after modifications. You can also ask IntelliJ to compile your program at any time, to check for any errors the compiler can detect automatically. Let’s try that now.

In IntelliJ’s menu, select Build → Build Module 'Subprograms' or press the corresponding shortcut key F10. (In IntelliJ, the command for compiling your code is known as building, a term that refers generally to preparing a program for use.)

After a moment, one of the following happens.

Either:

You don’t get any error messages, only a barely noticeable text at IntelliJ’s bottom-left corner: Build completed successfully. If this happened, great, but do make an intentional little formatting error in your code now and press F10 again, just to see the other possible outcome.

Or:

The Build tab pops up with one or more error messages. These messages are similar to the red-highlighted ones in the editor (but may be more comprehensive). You’ll need to fix your code. After fixing it, press F10 again.

Fixing errors and compiling your code

Before running a program you wrote, always make sure you’ve gotten rid of the errors highlighted by IntelliJ. If you don’t, the next step of testing your code will surely fail!

IntelliJ is quite clever: it catches many errors that prevent the code from running, right as you type. This is not foolproof, however, and some errors only show up when you compile the entire code.

Since IntelliJ compiles your code automatically when you run it — such as when you launch the REPL — it’s not necessary that you explicitly ask IntelliJ to compile. But it’s easy to just hit F10 whenever you feel like it and have your code checked by the compiler.

Testing your function

Start a REPL session with Ctrl+Shift+D, making sure that the Subprograms module loads up in the REPL. Note that in order to test your new code, you need a fresh REPL session.

Try calling your function with different parameter values. Does it work right? If not, return to Step 1 of Writing your code above. (Yes, to Step 1, not straight to Step 2.) Ask the O1 staff for help as needed.

(P.S. Did you notice that the result is expected in meters, not in centimeters?)

On “rebooting” the REPL

Whenever you edit your program and want to test the new version in the REPL, you need to load the new code into the REPL. You can either close the REPL and start it again or press the Rerun icon

in the REPL’s top left-hand corner. If you then wish

to re-enter some of your earlier commands, remember that you can

access them with the arrow keys.

in the REPL’s top left-hand corner. If you then wish

to re-enter some of your earlier commands, remember that you can

access them with the arrow keys.

Submit your solution

When you’re confident that your function works, enjoy the moment and submit your solution through IntelliJ.

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

More basic functions

If you like, you can build some programming routine with this optional practice task. It greatly resembles the previous assignment.

In the same file, week1.scala, write the following functions:

volumeOfCube, which expects a single parameter that represents a cube’s edge length and returns the cube’s volume. The parameter and the return value are bothDoubles.areaOfCube, which similarly computes and returns a cube’s total area, given its edge length. (That is, the function returns the area of the whole cube not just one of the cube’s sides.)

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

Defining Functions within the REPL

In the previous assignment, you used IntelliJ’s editor to write and save your functions in a separate file. That’s what we’ll be doing in upcoming assignments as well. However, it’s good to realize that you can also enter function definitions straight into the REPL:

def average(first: Double, second: Double) = (first + second) / 2average(first: Double, second: Double): Double average(2, 1)res2: Double = 1.5

This can be quite convenient when experimenting. However, using IntelliJ’s editor is better preparation for future assignments and makes submitting your solutions to A+ more convenient. Saving files in the editor also lets you keep the code you wrote.

As you experiment with Scala commands on your own, feel free to define functions in the REPL.

Practice on Functions and Modulo

The modulo operator

In addition to the everyday arithmetic operators, programmers commonly employ the modulo

operator, written in Scala as %. This operator is typically used with integer numbers;

for example, one might evaluate the expression 25 % 7.

Now go and experiment with the modulo operator on your own in the REPL.

Example: modulo and parity

For various reasons, it can be useful to determine a number’s parity: whether it’s even or odd. We might, for instance, wish to do something to every other element of a list, such as coloring the even and odd rows of a large table in a different background colors. Right now, we’re going to use parity simply as an additional example of defining a custom function and applying the modulo operator.

Let’s create an effect-free function that returns an Int. Our function will return zero

if the a given number is even; otherwise, it will return either 1 or -1, matching the sign

of the given number. Like so:

parity(100)res3: Int = 0 parity(2)res4: Int = 0 parity(103)res5: Int = 1 parity(7)res6: Int = 1 parity(-7)res7: Int = -1

The function can be readily implemented with the modulo operator: if we divide a number by two, we get a remainder of zero if and only if the number was even. Here’s a Scala implementation:

def parity(number: Int) = number % 2

Go ahead and define the function and experiment with it in the REPL. Or continue right away to the next assignment.

Chessboards: an introduction

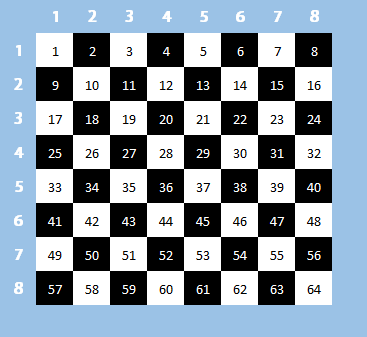

Let’s say we’ve numbered the squares on a chessboard from 1 to 64, starting at the top left and progressing from left to right, one row at a time. Moreover, we’ve numbered the rows and columns (ranks and files in chess lingo) from 1 to 8 each. There’s a picture right there.

If we know the number of a square, such as 35, how do we get the computer to work out which row and column the square is at? One possibility is to define two effect-free functions that can be used like this:

row(35)res8: Int = 5 column(35)res9: Int = 3

Here are the function definitions:

def row(square: Int) = ((square - 1) / 8) + 1

def column(square: Int) = ((square - 1) % 8) + 1

Chessboards: an assignment

But what if we instead numbered the squares from 0 to 63, and the rows and columns

from 0 to 7, as shown in this picture? Write two effect-free functions, row and

column, that work like this:

row(34)res10: Int = 4 column(34)res11: Int = 2

Instructions and hints:

Use the same workflow as in the

toMetersassignment.These functions, too, should go in

week1.scala.If you understand the versions above, where numbering starts at one, this is not likely to be a difficult assignment. Under the zero-based numbering scheme, the solution is actually simpler than the given versions.

Test your code in the REPL before you submit.

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

Consecutive Commands in a Function

Just to try out something, let’s create a function that prints out the same four lines

of text each time it’s called, followed by a fifth line that the function’s caller must

pass in as a parameter. We intend to be able to use our function, careerAdvicePlease,

like this:

careerAdvicePlease("I don't know what to do.")Oppenheimer built the bomb, but now he's dead. (Dead!)

Einstein was very, very smart, but not enough not to be dead. (Dead!)

So don't go into science; you'll end up dead.

Don't go into science; you'll end up dead.

I don't know what to do.

careerAdvicePlease("Such is the human condition.")Oppenheimer built the bomb, but now he's dead. (Dead!)

Einstein was very, very smart, but not enough not to be dead. (Dead!)

So don't go into science; you'll end up dead.

Don't go into science; you'll end up dead.

Such is the human condition.

Here is the function definition:

def careerAdvicePlease(addendum: String) =

println("Oppenheimer built the bomb, but now he's dead. (Dead!)")

println("Einstein was very, very smart, but not enough not to be dead. (Dead!)")

println("So don't go into science; you'll end up dead.")

println("Don't go into science; you'll end up dead.")

println(addendum)

The body of careerAdvicePlease contains multiple commands in

sequence. In cases like this, we write the commands on consecutive

lines. This means that each of the five println commands gets

executed, in order, whenever careerAdvicePlease is called.

This is also our first proper example of a code construct that is split over multiple lines. We indent (sisentää) the lines that make up the function body.

What about the return value?

Our careerAdvicePlease function returns the contentless Unit value — or

“returns nothing”, so to speak. That’s because the command in the function

body that is executed last determines the return value of the entire function.

In our example, the last command to be executed is the last of the printlns,

which yields only a Unit value (as discussed in Chapter 1.6). Therefore,

the same Unit value is also returned by the careerAdvicePlease function that

calls println.

Line Breaks and Indentations in Functions

We just saw that a function definition may span multiple lines, with some lines indented. This is more important than it might seem at first blush. Let’s take a closer look.

The importance of indenting right

Indentations are common to many programming languages. In some languages, indentations are completely optional and don’t affect a program’s behavior. Even so, it is commonly considered good style to indent one’s code, because the indentations bring out the program’s structure and make the code easier to read.

In other languages, indentations actually affect a program’s structure and behavior. Scala 3 falls in this second group: indentations aren’t just a matter of style. The code we wrote earlier wouldn’t work if we indented it haphazardly, like this for instance:

// This doesn’t work.

def careerAdvicePlease(addendum: String) =

println("Oppenheimer built the bomb, but now he's dead. (Dead!)")

println("Einstein was very, very smart, but not enough not to be dead. (Dead!)")

println("So don't go into science; you'll end up dead.")

println("Don't go into science; you'll end up dead.")

println(addendum)

Language versions are different

The explanation above applies to Scala’s modern version 3, which is what we use. In earlier versions of the language, indentation were optional. However, you had to write additional pairs of brackets around function bodies, and it was customary to indent the code anyway.

You may run into old-school Scala on websites or in dated books. There’s a bit more about this at the end of this page and in our style guide.

Indentation size

In Scala, it’s customary to use indentations that are two spaces wide, as in our original function and upcoming examples. But it’s possible to use a different indent width, as long as you’re consistent.

For example, here the indentations are seven spaces wide and the code works fine despite its unconventional style:

// Works, but this style is a bit odd.

def careerAdvicePlease(addendum: String) =

println("Oppenheimer built the bomb, but now he's dead. (Dead!)")

println("Einstein was very, very smart, but not enough not to be dead. (Dead!)")

println("So don't go into science; you'll end up dead.")

println("Don't go into science; you'll end up dead.")

println(addendum)

If you feel like a two-space indent is too narrow for you, feel free to adopt an indent width of four spaces, for example.

When should I indent?

In the careerAdvicePlease function, we broke the code onto multiple indented lines

because we wanted to group several print commands into a single function body. But

there is in fact nothing stopping us from using line breaks and indentation in smaller

functions, too. For instance, both these implementations of average do the same thing.

Version 1 (no line breaks):

def average(first: Double, second: Double) = (first + second) / 2

Version 2 (line break and indent):

def average(first: Double, second: Double) =

(first + second) / 2

Many Scala programmers follow these conventions:

If the function body contains multiple commands in sequence, write the line breaks and indent the body. This is what we did in

careerAdvicePleaseand Version 2 above.Also, if the function is effectful (e.g., it prints out something), split it across lines and indent as in Version 2, even if the function body consists of just one line.

However, if the function is effect-free (Chapter 1.6 and see below) and its body consists of just a single line, you can adopt the one-liner style. Version 1 is therefore a fine way to write

average. (That said, if the line becomes excessively long, it’s probably still better for readability to break it after the equals sign.)

To summarize: Version 1’s one-liner style is appropriate only if the function definition is a single, effect-free line of code that is not terribly long.

In this ebook, we generally follow those style conventions, and you may wish to do the same. You may find the conventions confusing at first, but don’t let that bother you when you’re writing your own programs. If it feels easier for you, go ahead and format all your functions as in Version 2. It’s always okay to break the line and indent the body!

How do I know if my function is effectful?

Picture this: your program is running and is in a particular state — certain things have been stored in memory and something is displayed onscreen. A function is then called. It does its job and produces a return value; a bit of time passes. Apart from that, is the program back in the state where it was before the function call?

If the called function is, say,

average, we are effectively back where we started: we obtained a result but nothing else changed. This is an effect-free function.If the called function is, say,

println, we are not back to the original state: the program has generated a line of output. This is an effectful function.

Here’s another way to think about it: if you knew the return value of the function

already, would it even be necessary to call the function? In the case of our effect-free

averaging function, the answer is no: we could have just as well have replaced the call

average(5, 10) with the literal 7.5. In the case of the effectful println, on the

other hand, we don’t get any printing done without calling the function.

You may mark where a function body ends

Sometimes, it’s good to be extra clear about where a function’s code ends. Scala gives you a tool for this: you can write an end marker (loppumerkki) at the end of a function body. Our earlier example functions could also be written like this:

def average(first: Double, second: Double) =

(first + second) / 2

end average

def careerAdvicePlease(addendum: String) =

println("Oppenheimer built the bomb, but now he's dead. (Dead!)")

println("Einstein was very, very smart, but not enough not to be dead. (Dead!)")

println("So don't go into science; you'll end up dead.")

println("Don't go into science; you'll end up dead.")

println(addendum)

end careerAdvicePlease

An end marker begins with the word end. When we’re ending

a function definition, like here, we follow end with the

function’s name. Note that the end markers aren’t indented

deeper but aligned with the corresponding defs.

The purpose of end markers is not to modify the program’s behavior but to assist human readers. But most of the time you don’t really need an end marker to tell where a function ends, so people often don’t write these markers on functions. In this ebook, too, we’ll usually not write them, although you’re free to do so if you prefer.

Assignment: Text Accompanied by Music

Task description

Write an effectful function called accompany that prints out a line of text and

plays a sound to go with it. The function should take two parameters, each of which

is a string: the function prints out the first string and plays the second.

When you’re done, you should be able to use the function as in this example.

accompany("Nananana nananana nananana nananana BATMAAN!",

"[49]<" + "(d<g>)(d<g>)(db<g>)(db<g>)(c<g>)(c<g>)(c#<g>)(c#<g>)" * 2 + "[54]>(FG)-.(FG)---/160")Nananana nananana nananana nananana BATMAAN!

accompany("... and introducing acoustic guitar",

"[26] >EF#A---G#---F#---E---F#G#---------EF#A---G#---F#---E---F#EF#---------/192")... and introducing acoustic guitar

The line breaks in the example are there just to prevent overlong lines. They aren’t strictly necessary.

Instructions and hints

Write your solution in the same file,

week1.scala.Pick sensible names for the parameter variables.

In this assignment, it doesn’t matter whether you call

printlnorplayfirst. Take your pick, as long as you do both.The

playfunction has been defined so that it plays the notes in the background and the computer doesn’t wait for the sound to finish before executing the next command. So the printout will appear right away, even if you place theplaycommand before theprintln.

Follow the style guidelines above: split your code over multiple lines.

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

Tools for Building New Functions

The preceding examples have shown that when you implement a function body, you can apply

the programming techniques you know from earlier chapters: arithmetic operators, println,

play, and so on. Other familiar commands work, too. For instance, a bit further down in

this chapter, we’re going to define new variables within a function.

Throughout O1, you’ll learn additional tools for building your own functions: you’ll be able to make functions choose between alternatives, execute commands repeatedly, and so on.

One common thing to do in a function is to call another function. For instance, we can

use the hypotenuse function from package scala.math to create a function that determines

the distance between two points (x1,y1) and (x2,y2):

def distance(x1: Double, y1: Double, x2: Double, y2: Double) = hypot(x2 - x1, y2 - y1)

The picture functions from package o1, introduced in Chapter 1.3, are also available to

us as we create new functions:

A picture-creating function

This function produces red “balls” of different sizes:

def redBall(size: Int) = circle(size, Red)

A usage example:

val ball = redBall(50)ball: Pic = circle-shape val biggerBall = redBall(300)biggerBall: Pic = circle-shape show(biggerBall)

Vertical bars

In week1.scala, create a function called verticalBar that forms pictures of

blue rectangles that are ten times as many pixels high as they are wide.

The function should take a single parameter of type Int, namely the width of the bar.

Here’s a usage scenario:

val picOfBar = verticalBar(80)picOfBar: Pic = rectangle-shape show(picOfBar)show(verticalBar(180))

Give a meaningful name to the parameter variable. Use show to test your function in the

REPL.

Please note that your function must not call show and display the picture; it must

return the picture. Then you’ll be able to use your function and show in combination

as illustrated above.

If you need a recap on how to create shapes, check back to Chapter 1.3.

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

An overloaded function

Continue from the previous assignment by creating another verticalBar function. That

is to say, do not erase the original you just wrote but add another function with the

same name. This new function should take two parameters, a width (Int) and a color

(Color). It should be usable like this:

val blackBar = verticalBar(80, Black)blackBar: Pic = rectangle-shape show(blackBar)

Clearly, this second verticalBar function will be more flexible — more abstract! —

as far as color is concerned, since it lets the user pick the color. On the other hand,

it requires its caller to pass in an additional parameter. This second function, too,

returns a picture that’s ten times as high as it’s wide.

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

As you see, Scala allows us to define multiple functions with the same name, even in the same context. This is called overloading (kuormittaa) the function name. Overloading is allowed only if the functions that share a name differ in which parameters they take.

Even though the two verticalBar functions share a name, they are completely distinct

from each other. When you use the functions’ name, Scala figures out which one you mean

based on the parameters you provide.

Practice Understanding Functions

Local Variables

Example: tax rates

Let’s write an effect-free function that calculates how much income tax one has to pay under the following system of taxation:

Up to a specific threshold, the taxpayer must pay a base percentage of their income as tax (e.g., 20 percent), as set by the government.

In addition, they must pay a higher percentage (e.g., 40 percent) of all that they earn above the threshold (if anything).

We want our function, incomeTax, to take four parameters: the earner’s total income,

the threshold income, the base rate of taxation, and the additional rate, as shown below.

incomeTax(50000, 30000, 0.2, 0.4)res12: Double = 14000.0 incomeTax(25000, 30000, 0.2, 0.4)res13: Double = 5000.0

We could define this function as a one-liner whose body consists of a single expression that evaluates to the function’s return value. But we can do better than that. Let’s store intermediate results in variables so that our code is a bit neater:

def incomeTax(income: Double, thresholdIncome: Double, baseRate: Double, additionalRate: Double) =

val baseTax = min(thresholdIncome, income)

val additionalTax = max(income - thresholdIncome, 0)

baseTax * baseRate + additionalTax * additionalRate

We define two local variables (paikallinen muuttuja) and assign intermediate results to them.

Recall that when a function consists of multiple commands, the last command determines the return value of the function. Our example function returns the value of the arithmetic expression on the last line. The two lines above it set up that final expression.

Local variables are accessible only within the program code of the function itself.

A function’s caller doesn’t need to be aware of the called function’s local variables —

and couldn’t access them even if they were. Any user of incomeTax, for instance, can

remain blissfully unaware of what the function’s local variables are called, or even that

there are any local variables there to begin with.

And the following attempt to tamper with the function’s internal variables is unsuccessful,

irrespective of whether we have previously called incomeTax.

additionalTax * additionalRate-- Error: |additionalTax * additionalRate |^^^^^^^^^^^^^ |Not found: additionalTax

In fact, the local variables don’t even exist during the entirety of the program run but only while the function is being executed. Local variables are created within the frame associated with the function call on the call stack. As soon as the function call is over, any memory reserved for the local variables is released for other use. This is depicted in the animation below.

More function-reading practice

Exercise: Course Grades

Task description

Program an effect-free function that determines a student’s overall course grade according to a particular grading policy. In our imaginary course, the overall grade is the sum of a project grade (between 0 and 4), a bonus from an exam (0 or 1), and a bonus for active participation (0 or 1). However, the overall grade can never exceed 5.

Your function must adhere to the following specification.

Its name is

overallGrade.As parameters, it expects three integers: a project grade and the bonuses for exam and participation, in that order.

It returns the resulting overall grade between 0 and 5, also as an integer. (It doesn’t print the grade but returns it.)

You must ensure that even if the sum of the components is more than five, the overall grade isn’t. However, you don’t need to concern yourself with what happens if someone were to call your function on invalid parameter values (such as a negative project grade or an excessive exam bonus).

Instructions and hints

Once again, write your code in week1.scala.

Follow the now-familiar workflow summarized below.

Make sure you understand precisely what the function is supposed to do!

Implement the function in stages: name, parameter variables (with sensible names!) and their types, function body.

Reset your REPL.

Test your function on a variety of parameter values. Go back to Step 1 if needed.

Submit your program only when you’re satisfied that it works.

Chapter 1.6 introduced a mathematical function — one that we already used in this chapter, too — and that you’re likely to find useful.

(Tip: If you experiment with the math functions in the REPL, remember to import

scala.math.*. That import already appears at the top of week1.scala, so the math

functions are available in that file.)

A+ presents the exercise submission form here.

The package Keyword

The Scala file you’ve been editing begins with the word package, like this:

package o1.subprograms

The meaning is fairly self-evident: the package keyword is used at the top of each

Scala file to mark which package the contents belong to.

These package definitions are necessary but unnoteworthy. They’ve been largely omitted

from the code fragments in this ebook text. They are included in the IntelliJ modules,

though; during O1, you’ll see these definitions at the top of many files.

Good to Know: Versions of Scala

In this chapter, we’ve written code like this:

def incomeTax(income: Double, thresholdIncome: Double, baseRate: Double, additionalRate: Double) =

val baseTax = min(thresholdIncome, income)

val additionalTax = max(income - thresholdIncome, 0)

baseTax * baseRate + additionalTax * additionalRate

That’s the sort of code that we’ll keep writing, too. However, if you explore Scala pages out there on the internet, you’ll also run into code that looks like this:

def incomeTax(income: Double, thresholdIncome: Double, baseRate: Double, additionalRate: Double) = {

val baseTax = min(thresholdIncome, income)

val additionalTax = max(income - thresholdIncome, 0)

baseTax * baseRate + additionalTax * additionalRate

}

The difference here is the curly brackets around the function body. You may run into other differences as well.

This has to do with language versions. In O1, we’re using the up-to-date version of the language, Scala 3, which was released in 2021. There are many websites and books out there that don’t. In older versions of Scala, you had to write curly brackets in a lot of places, and there were some other differences in syntax too.

Our style guide says a bit more about this. We recommend that you read that guide at some point reasonably early in O1, but not necessarily now. Around Week 3 would be good, for example.

Summary of Key Points

A function definition includes the function’s name, its parameter variables and their data types, and a function body. All in all, it is an implementation of an algorithm that takes care of whatever the function is expected to do.

When a function call starts, the computer reserves a so-called frame of memory to keep track of the call.

The parameter values that the function receives are stored in variables within the frame.

You can also define additional variables in the frame. Such a variable is known as a local variable.

Frames form a call stack (which we’ll discuss further in the next chapter).

Links to the glossary: function, function call, function body, end marker; frame, call stack; local variable, parameter variable, to overload.

The diagram below includes a handful of concepts that are central to how functions work on the inside.

Feedback

Please note that this section must be completed individually. Even if you worked on this chapter with a pair, each of you should submit the form separately.

Credits

Thousands of students have given feedback and so contributed to this ebook’s design. Thank you!

The ebook’s chapters, programming assignments, and weekly bulletins have been written in Finnish and translated into English by Juha Sorva.

The appendices (glossary, Scala reference, FAQ, etc.) are by Juha Sorva unless otherwise specified on the page.

The auto-grading of the assignments has been developed by the following Aalto students (in alphabetical order): Riku Autio, Kai Bukharenko, Nikolas Drosdek, Kaisa Ek, Rasmus Fyhrqvist, Joonatan Honkamaa, Antti Immonen, Jaakko Kantojärvi, Onni Komulainen, Niklas Kröger, Kalle Laitinen, Teemu Lehtinen, Mikael Lenander, Ilona Ma, Jaakko Nakaza, Strasdosky Otewa, Kaappo Raivio, Timi Seppälä, Teemu Sirkiä, Onni Tammi, Joel Toppinen, Anna Valldeoriola Cardó, and Aleksi Vartiainen.

The illustrations at the top of each chapter and the similar drawings elsewhere in the ebook are the work of Christina Lassheikki.

The animations that detail the execution Scala programs have been designed by Juha Sorva and Teemu Sirkiä. Teemu Sirkiä and Riku Autio did the technical implementation, relying on Teemu’s Jsvee and Kelmu toolkits.

The other diagrams and interactive presentations in the ebook are by Juha Sorva.

The O1Library software has been developed by Aleksi Lukkarinen, Juha Sorva, and Jaakko Nakaza. Several of its key components are built upon Aleksi’s SMCL library.

The pedagogy of using O1Library for simple graphical programming (such as Pic) is

inspired by the textbooks How to Design Programs by Flatt, Felleisen, Findler, and

Krishnamurthi and Picturing Programs by Stephen Bloch.

The course platform A+ was originally created at Aalto’s LeTech research group as a student project. The open-source project is now shepherded by the Computer Science department’s IT services; the project has received contributions from dozens of Aalto students and others.

The A+ Courses plugin, which supports A+ and O1 in IntelliJ IDEA, is another open-source project. It has been designed and implemented by various students in collaboration with O1’s teachers.

For O1’s current teaching staff, see Chapter 1.1.

Additional credits for this page

The “career advice” comes from The Arrogant Worms.

A function definition begins with the

defkeyword followed by a name for the function, which is chosen by the programmer. In Scala, it’s customary to start function names with a lower-case letter, just as we did earlier with variables.